The jubilation at the end of World War II in September of 1945 fueled a hunger for commemorative illustration, and N. C. Wyeth, along with Norman Rockwell, rose to the occasion. Rockwell produced his own picture of a G.I. coming home from the war for the Saturday Evening Post. He used an even tighter cropping of a similar composition in 1948, the open-ended Homecoming. These share an urban setting and the warm embrace of family and neighborhood characters, and they are certainly among the most memorable images of Americans returning from Europe.

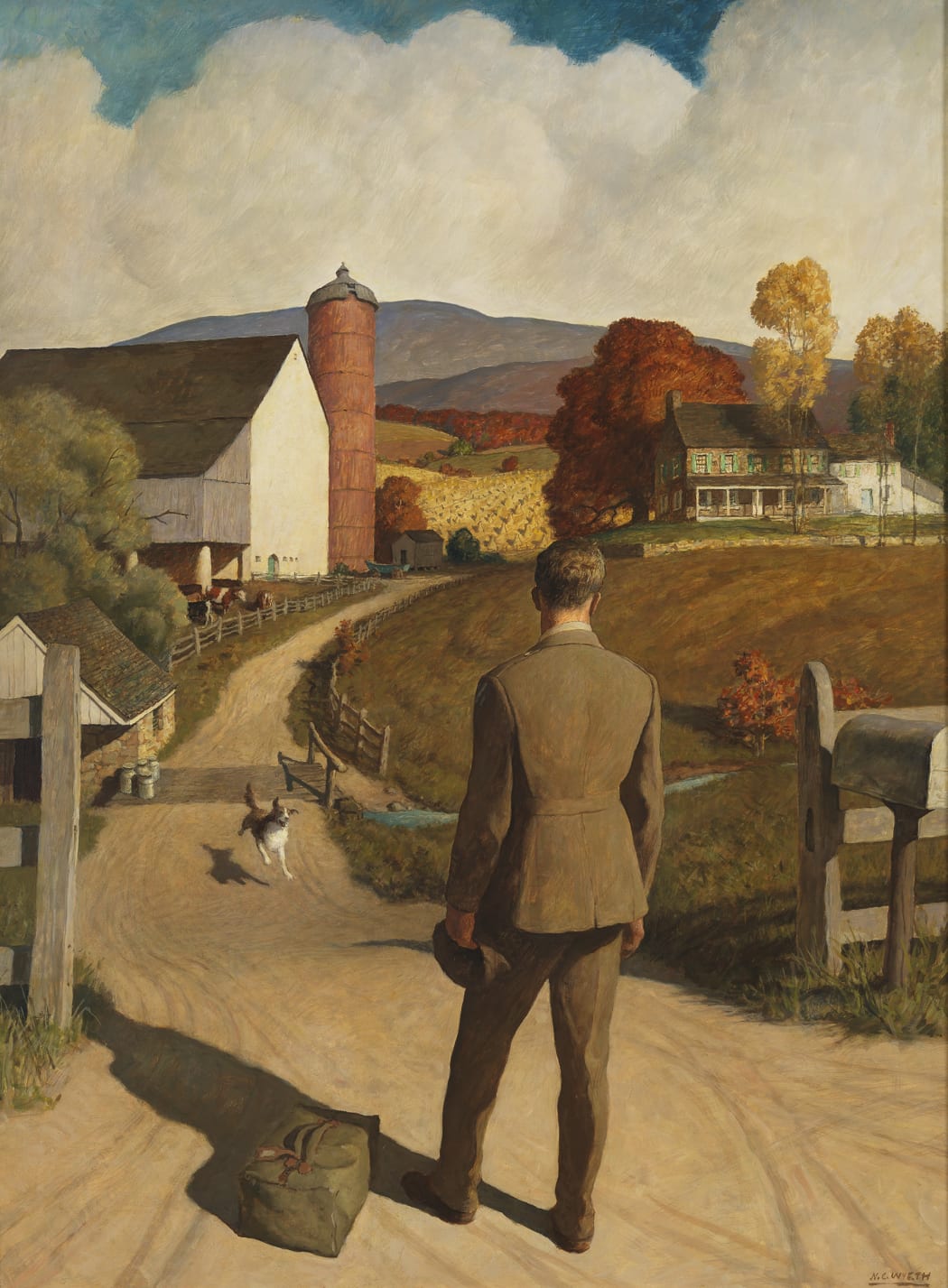

When N. C. Wyeth was commissioned by Women’s Day editor Kirk Wilkinson for his own Post-war reunion picture, he adopted a similar concept, but filled the composition with his own stamp of pure Americana. The process began with an over-scale drawing in charcoal. It has been suggested that none other than Andrew Wyeth posed as the model for this composition, but, with the figure’s back to us, he is idealized and rendered anonymous—any parent’s son returning from war.

The editors of Women’s Day reviewed the drawing and made a few minor suggestions:

“The soldier should appear to be younger and slimmer, typically G.I. and in an absolutely authentic and well-fitting uniform and with a G.I. haircut. His bag should be a standard regulation canvas” [Christine B. Podmaniczky, N. C. Wyeth Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings (2008) vol. 2, p. 593].

Adding to these changes, Wyeth also straightened his subject from the dynamic pose of bent knees and outstretched arms to a stiffer posture of resolve. In the final composition, the returning infantryman seems almost to hesitate—happy to be home, certainly, but overwhelmed, perhaps even bearing some of the weight of his time at the front.

The subtle psychological layering of this posture elevates Wyeth’s opus to a level of art beyond illustration. Alexander Nemerov described this subtlety:

“N.C. Wyeth, in his large drawing entitled Soldier’s Return, also made a picture about death-in-life near war’s end—one that employs the same rhetoric Rockwell used in Homecoming G.I.. The scene, like Rockwell’s, is ostensibly happy. The lone soldier has come back to the family farm. His dog races to greet him, as in Rockwell’s picture. The soldier has dropped his bag unlike Rockwell’s weighted figure, releasing his wartime burden at the threshold of the farm so that he can accept with open arms the life he used to know. The property is still in perfect shape” [Alexander Nemerov, “Coming Home in 1945, Reading Robert Frost and Norman Rockwell,” American Art, (2004), p. 67].

An even greater difference from the Rockwell picture is Wyeth’s “background”: arguably the true subject of the painting. Rockwell’s homecomer is greeted by urban cacophony, while Wyeth’s is met by rural stillness, puncuated only by the jubilant dog. With the figure’s back to us, we take in the scene with his eyes, as if America itself, rather than a red-brick row-house, were welcoming us home. Wyeth’s fine art work in the preceding decades had placed him as a chronicler of Americana in rough alignment with Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. His America was not quite a wild one, but certainly a rural Regionalist one. The crisp, rolling hills are more akin to the work of Grant Wood than to Norman Rockwell. The sumptuous forms and the suggestion of a nostalgic view of a bygone, bountiful America, heighten the warmth of the subject’s return.

The return from wartime to farmland in particular was poignant for Wyeth: it is the subject of among the most famous American paintings of all time, Winslow Homer’s The Veteran in a New Field. Here, too, the returning veteran stands with his back to us, surrounded by his the agrarian pursuit. There is a stirring ambivalence in the figure’s posture. Peacetime harvest is certainly a happy thing, and Homer, Wyeth, and Rockwell alike celebrated the end to their respective wars. But Homer’s painting, like Wyeth’s, is slightly haunted. The farmer’s scythe is presented like Death’s, leaving a reverberation of the horrors of that bloodiest of American wars, far from forgotten in 1865. Wyeth’s Homecoming is certainly cheerier, but the faint reluctance of the man’s posture hints at unforgettable experiences. A man returning to a farmhouse he left as a boy. His burden is at his feet, but it is with him. Wyeth was well acquainted with the painting and a devoted follower of Homer, even naming his home in Maine after one of Homer’s paintings.