In 1965, at 19, artist Jamie Wyeth left the home of his parents, Andrew and Betsy, in Chadds Ford for New York City, where he immersed himself in the city’s art scene — and visited its morgues to study human anatomy.

The city was also where he made an unlikely friend in Andy Warhol.

In 1975, the artists, in their vastly different styles, painted portraits of one another in a face-off. Warhol’s portraits of Wyeth “made me look a bit too glamorous,” Wyeth said to the New York Times in 2017. He returned the favor by painting the Patriarch of Pop in his trademark realistic style, complete with blemished skin and disheveled hair.

Those portraits became the 1976 exhibition “Andy Warhol and Jamie Wyeth Portraits of Each Other” at New York’s Coe Kerr Gallery. Two are now in the permanent collection of D.C.’s National Portrait Gallery.

And at least 11 of Wyeth’s portraits of Warhol made it into a box that Wyeth’s wife, Phyllis, stashed away at the back of her closet. It would remain unopened until 2022, three years after Phyllis Wyeth’s death in 2019.

“The Stash,” found by Jamie Wyeth while cleaning his Chadds Ford home, also held portraits of Soviet ballet dancer and choreographer Rudolf Nureyev, Warhol’s manager Frederick W. Hughes, and actress Candy Darling — most drawn between 1976-77, spontaneously, hurriedly.

“She stole them from me,” Wyeth said of his wife, with a laugh. “When I was working on those, I was in a frenzy. And I didn’t keep track of where things went, and she was particularly interested in Nureyev.”

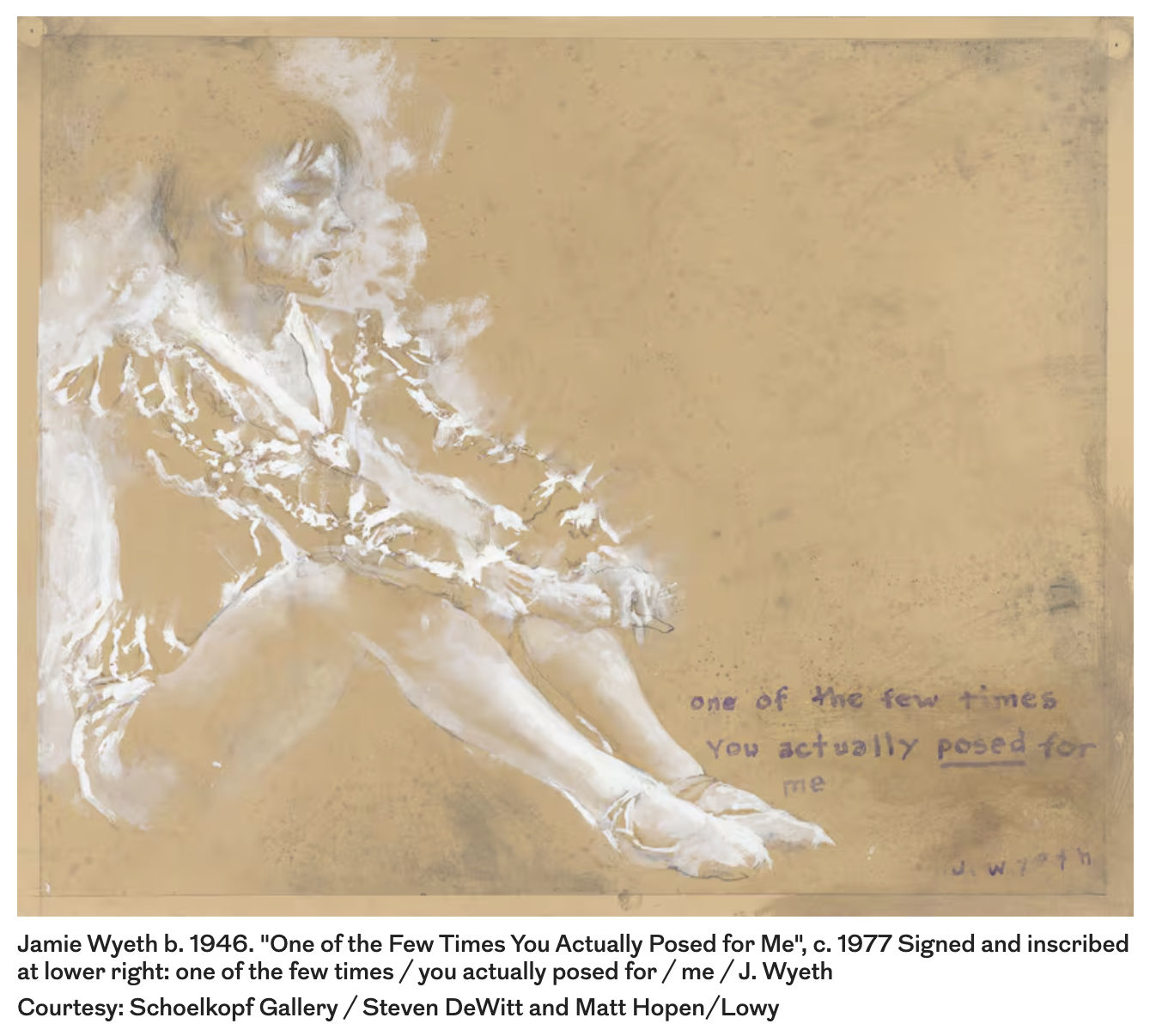

Nureyev, who was born in 1938 on a Trans-Siberian train near Lake Baikal, was often seen at Warhol’s Factory and the legendary Studio 54 discotheque. Wyeth first saw him at a dance recital and then at a friend’s house in New York.

“He strode in and all conversation came to a stop. At the end of the evening, I said, ‘Would you ever let me do some studies of you?’ He said, ‘Of course not. I have no time,’” said Wyeth, trying his best Russian accent.

After a year, the dancer was ready.

“That began a two-year involvement of bird-dogging him around,” said Wyeth.

Phyllis Wyeth eventually became “great friends” with Nureyev.

“It’s very interesting, her point of view. To me, that’s the most fascinating part of it, what she chose [to hide]; which are rather unusual ones of both [Warhol and Nureyev],” said Wyeth.

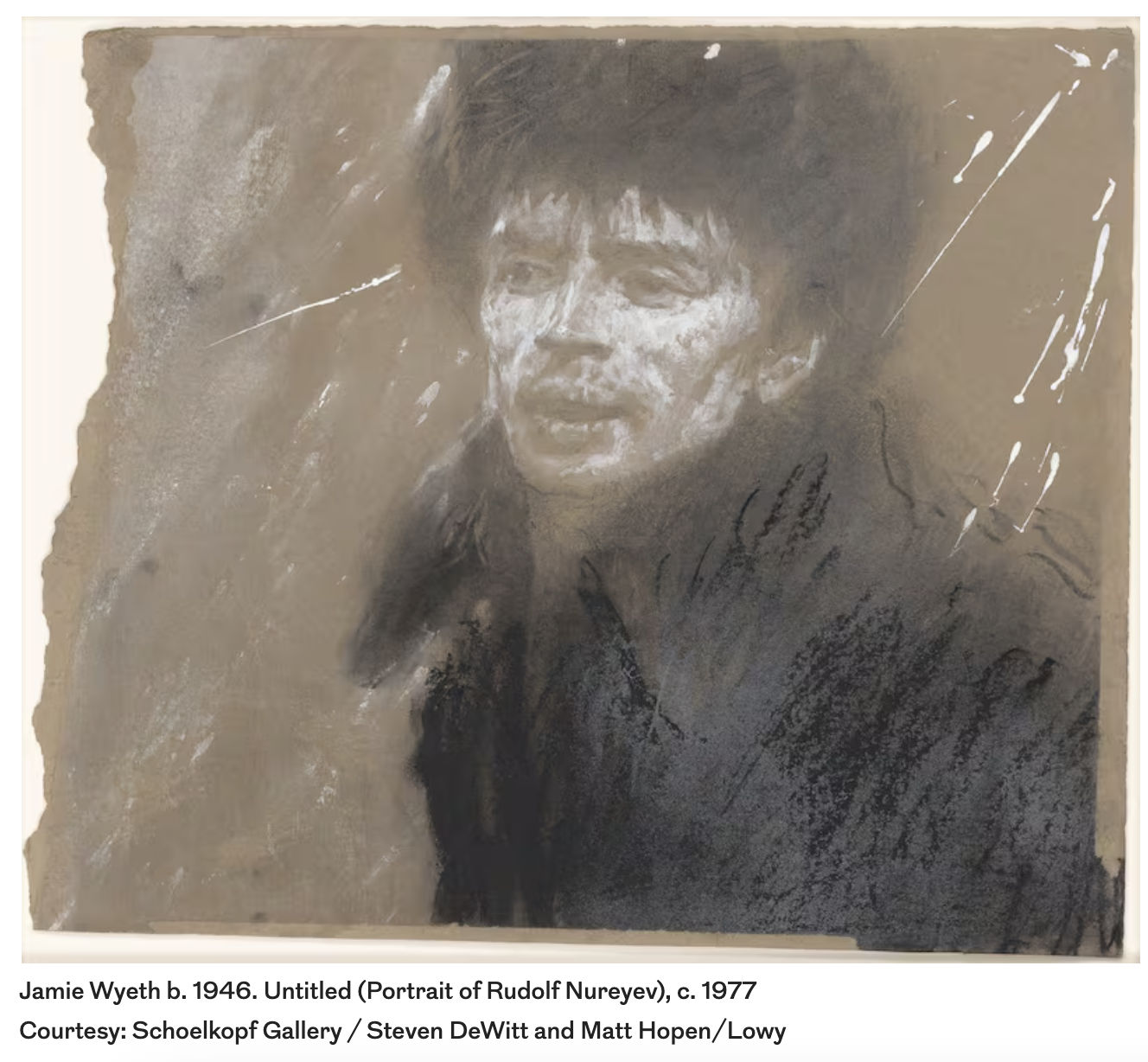

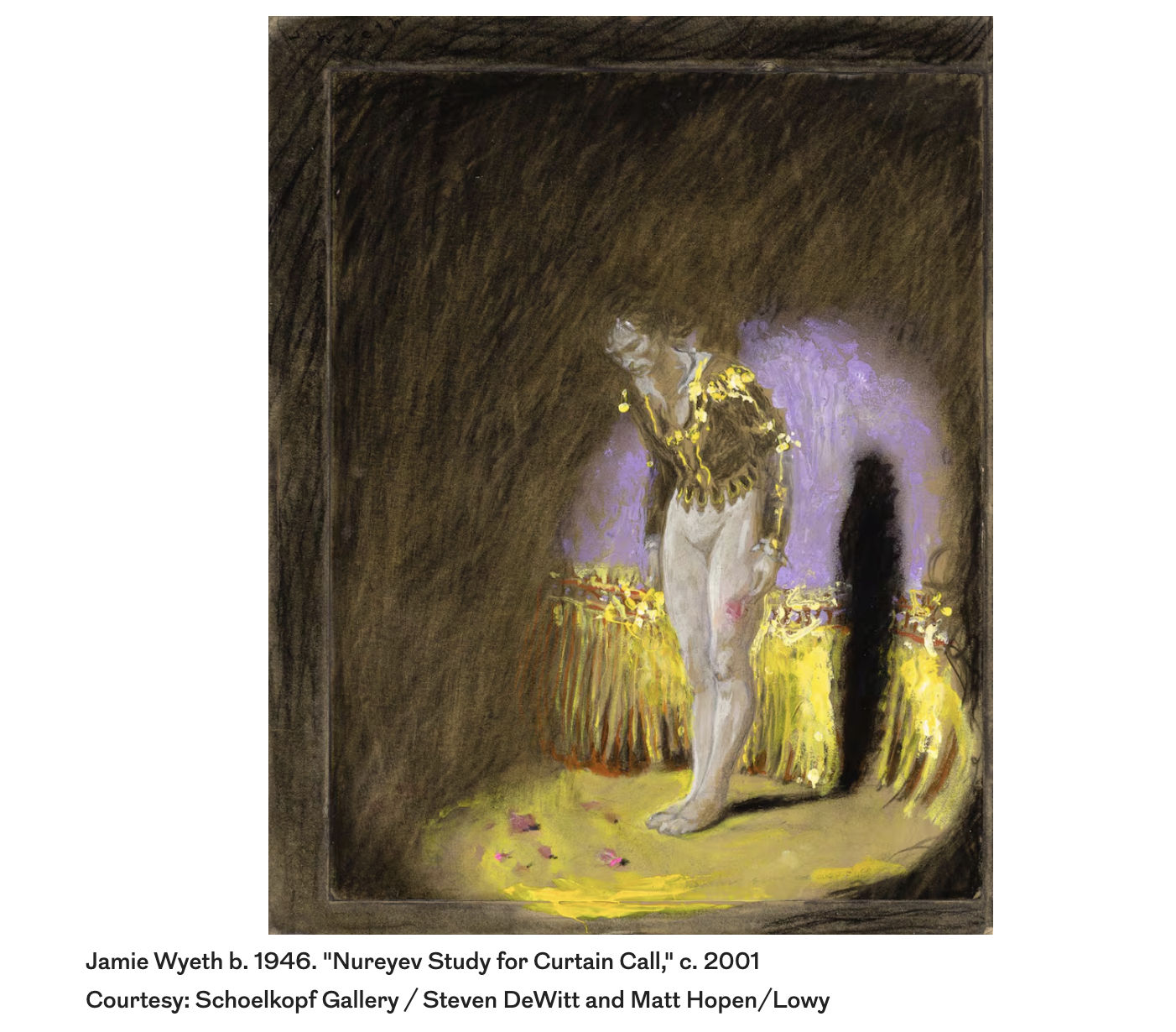

Several of Nureyev’s portraits in the Stash are of him in his ballet regalia — with an outstretched arm, applying makeup, taking a bow at curtain call, all drawn in rushed strokes on cardboard, seemingly in motion.

“I don’t have somebody sit frozen in a chair. I follow them around and see them in different circumstances,” Wyeth said.

The ones that stand out are of Nureyev wearing a fur coat and an astrakhan hat: calmer, looking at the artist, and less in a hurry. One, titled Hands on Hips, in Fur, Nureyev (Study #25) (1977), has him posing in the unbuttoned coat with no shirt underneath, his hands on his hips.

“[Nureyev] would come down and visit [Chadds Ford] on weekends. Once he went out in a horse and carriage with a cousin of Phyllis’. This was in November, and it started sleeting. I looked back and he was sitting wrapped in furs. It was straight out of the steppes of Russia. It was just unbelievable. My hair is standing on its end,” said Wyeth, as he recounted the scene.

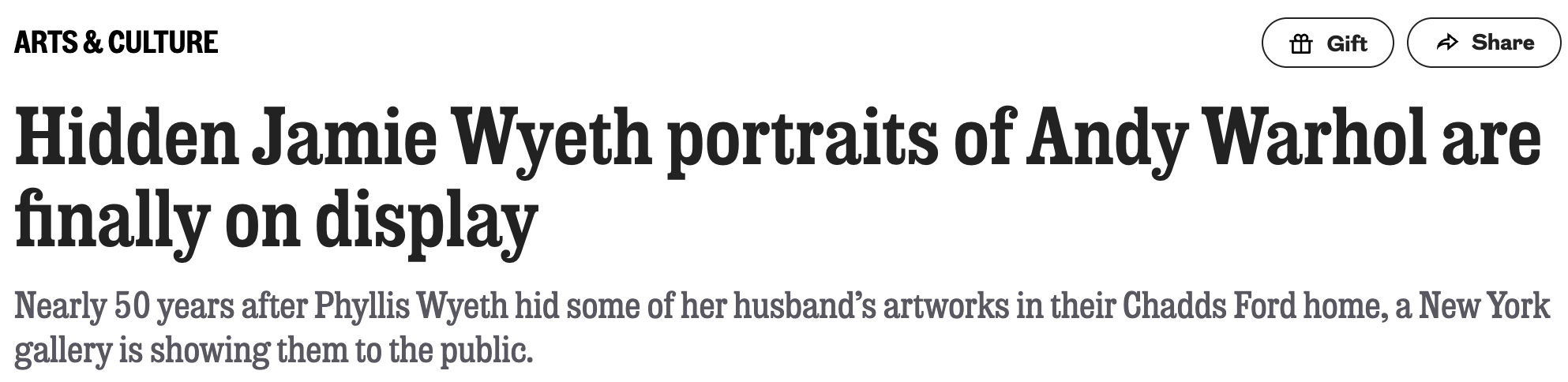

Another 1977 portrait of Nureyev sitting on the floor in a ruffled leotard is inscribed “one of the few times / you actually posed for / me / J. Wyeth.”

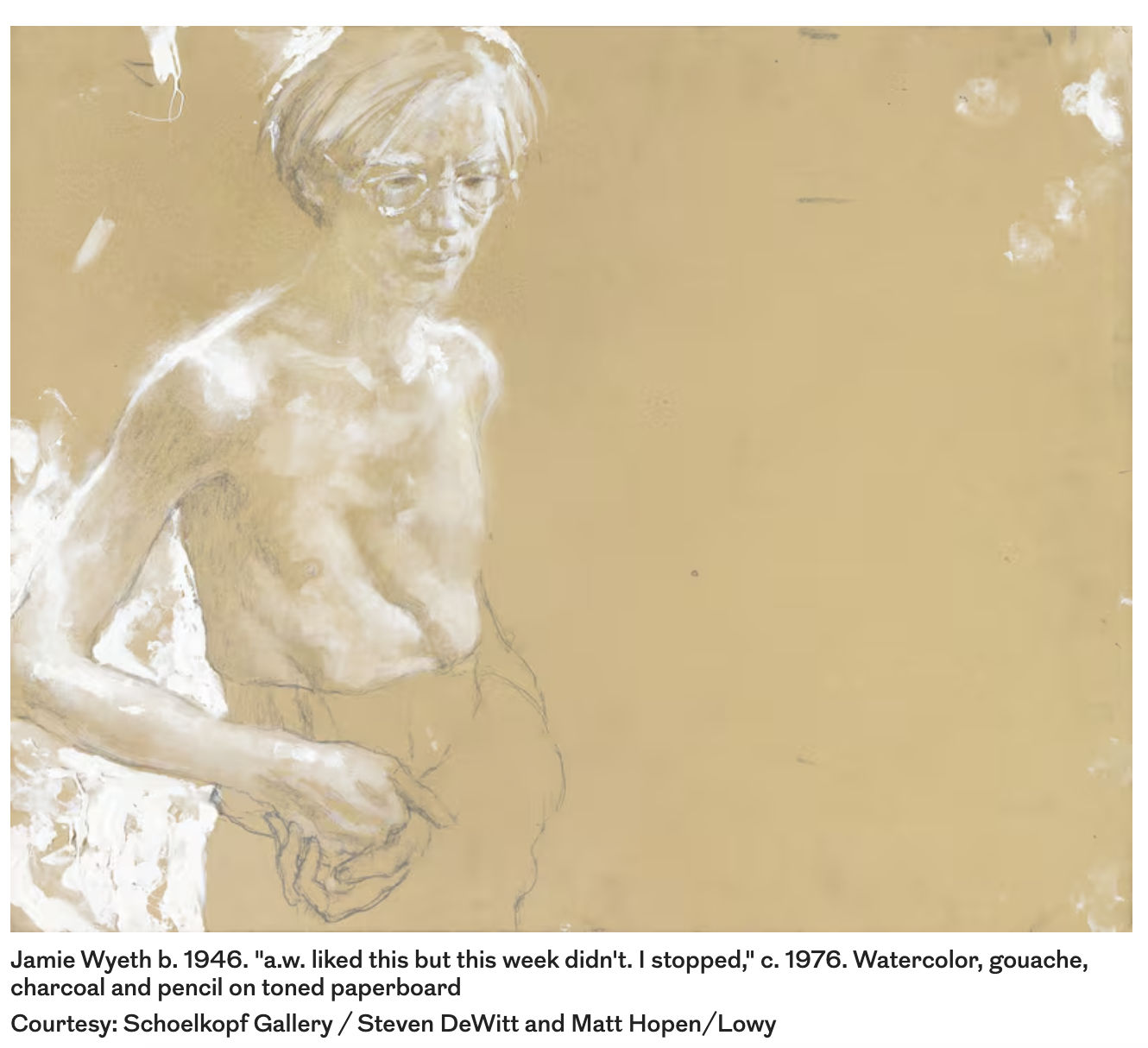

The portraits of Warhol, too, are out of the ordinary — none of the glam shots in sunglasses we often see. A 1976 watercolor, gouache, charcoal, and pencil portrait of the artist standing shirtless is especially vulnerable. His torso, outlined in white, shows the scar from the gunshot wound from a failed assassination attempt in 1968. The inscription reads: “a.w. liked this but this week didn’t. I stopped.”

“I was trying to recall what I was talking about,” said Wyeth, “I think it was really more about Fred Hughes. He saw the drawing and said, ‘You know, let’s not go there.’ As I recall it, that’s why I stopped on that thing. I mean, here was this little, thin figure with these terrible scars … it was a very vulnerable image of him.”

“I spent a lot of time with both of them” and finding the art “ported me to my life back then … So it brought all that back, too.”

“Well, I thought they were joking,” said Schoelkopf, who rushed to Chadds Ford earlier this year to see the portraits for himself. But first, he had to sit through lunch with a Nureyev portrait hanging by the table. “And I was just like, ‘Jamie, come on man, we gotta go,’” said Schoelkopf, who has previously exhibited Andrew Wyeth’s works.

“I can’t help myself. I’m an art dealer. And what every art dealer wants, let’s be honest, is discoveries around new bodies of work. It’s just the most fun,” he said.

Adelson and Schoelkopf got the paintings to framers and, earlier this month, they arrived at the Schoelkopf Gallery where they are part of the “Jamie Wyeth: Portraits of Andy Warhol and Rudolf Nureyev” that opened this week.

It features Wyeth’s works from every decade from the 1960s to some of his most recent works that he finished months ago. This is Wyeth’s first major show since his wife’s death.

When I spoke to him in late August, our phone call found a background score in the call of gulls flying outside his window in Maine. He was painting them as we spoke.

“I’m terrified to have shows,” said the artist, 79, who had his first show at age 20. “It’s not a pleasant experience for me. You feel like a fool standing there and seeing all my inadequacies scream out. I tell writer friends of mine, it’s like you walk into a room and everybody’s reading your new poem or novel. You feel very, very vulnerable.”

Does he think his wife set him up by “stealing” the art that forms the core of the new show?

“I think she was just worried that I was going to sell them, and she wanted to keep them.”

The New York show, Schoelkopf said, had received more than 100 preview requests from buyers in the first 48 hours since it was announced.

“I have too much of my own work around, and I’m tired of looking at my own work,” said Wyeth. “I still have many others that she wanted, that I gave to her.”

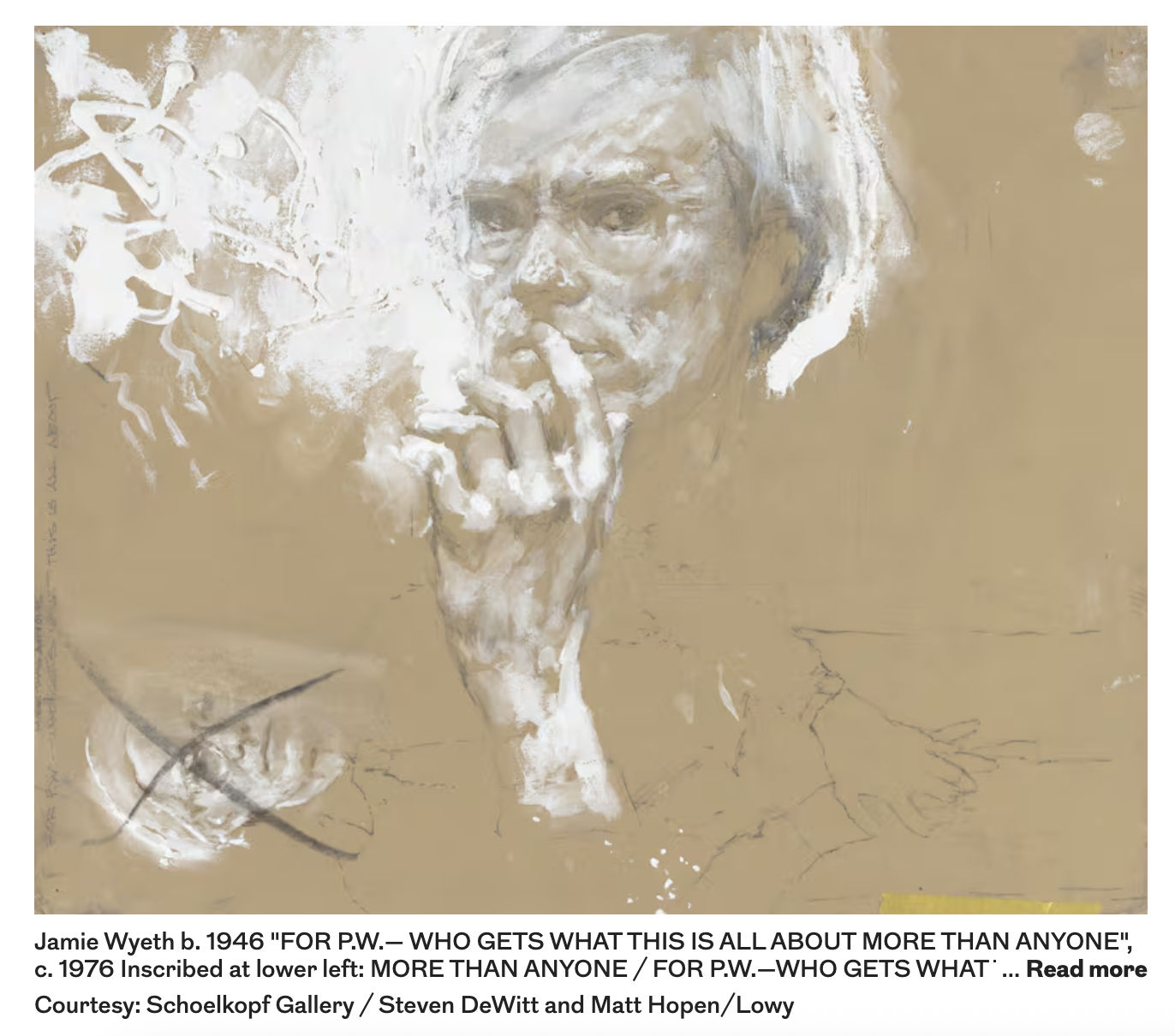

An artwork from the Stash has two portraits of Warhol in white: a scratched-out horizontal one of a ghostly shadow of an unfinished body, and one of the artist with his shock of white hair and a part of his hand visible in contemplation.

Inscribed on the lower left in Wyeth’s handwriting are the words: “More than anyone / For P.W.— who gets what this is all about.”

Phyllis Wyeth, described as a “superstar” by Schoelkopf, seems to have gotten it all along.