The rediscovered cache of works also includes Wyeth's previously unseen drawings of Rudolf Nureyev.

by Min Chen

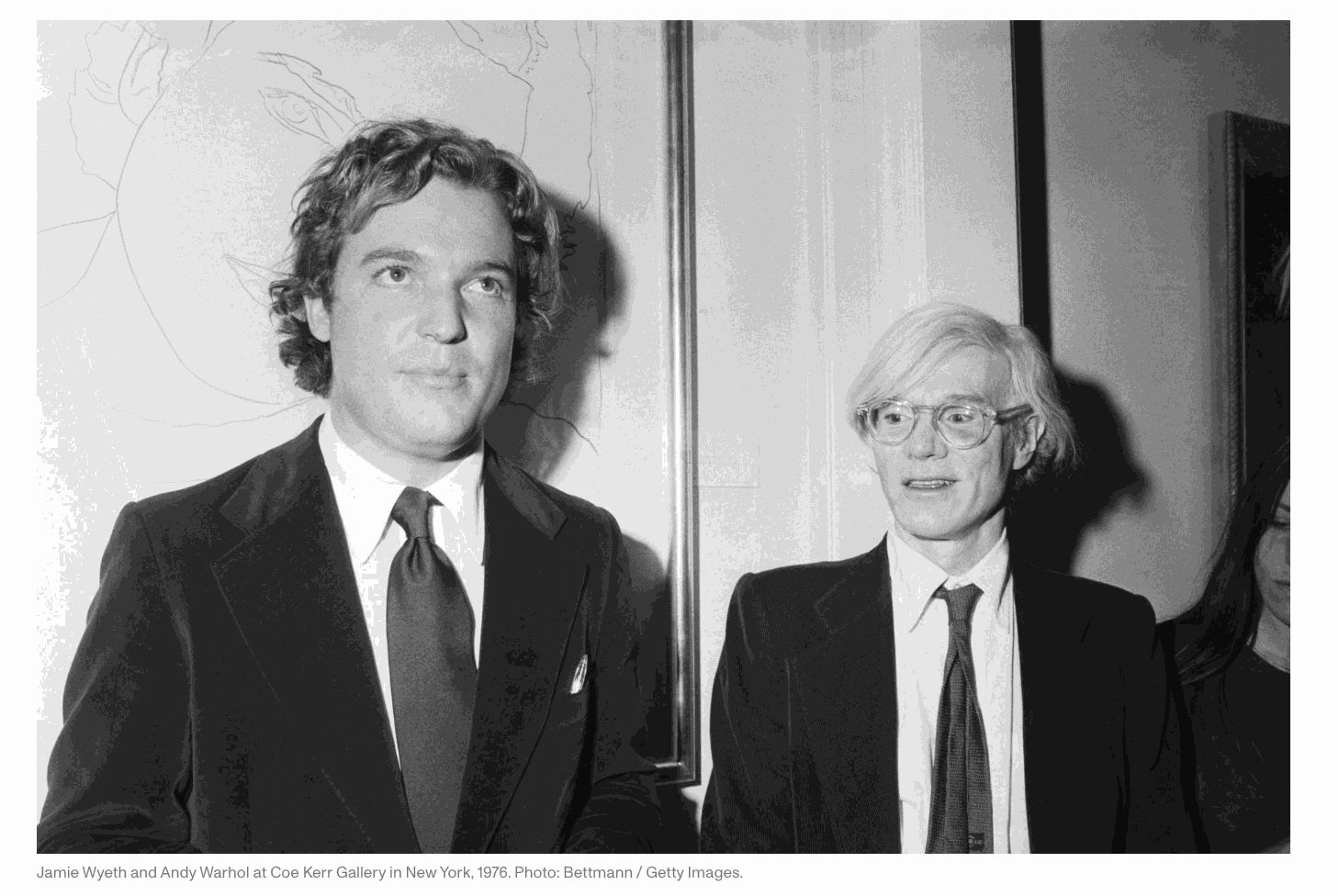

In 1976, Coe Kerr Gallery in New York opened an exhibition of an unlikely pairing. Jamie Wyeth, realist painter, and Andy Warhol, the high priest of Pop, were showing portraits and drawings they had created of each other. Amid the 36 works on view were Warhol's high-glamor canvases of Wyeth sitting alongside Wyeth's tender depictions of Warhol posing with his darling dachshund Archie. By the end of opening night, half the pieces had been snapped up.

That outing emerged from Wyeth and Warhol's budding connection. However dissimilar on the surface-one the third-generation scion of a celebrated painting dynasty known for his scenes of rural Delaware and Maine; the other a Pop pioneer, who, at his New York-based Factory, crafted silkscreened critiques of consumerism-they formed a surprising kinship in the 1970s that would endure for years.

"He just was right up my alley," Wyeth recalled over a phone call. "Here he was, sort of in costume, and I found him to be childlike. I think we spent a lot of our time in toy stores." (Warhol, for his part, once reflected of Wyeth: "I always wished I could paint like him.")

When not toy shopping, the pair exchanged portraits. In fact, so avidly did they sketch each other that eight years after Warhol's death, Wyeth was stunned to hear about an exhibition of previously unseen drawings that the Pop artist had made of him.

"There were all these huge drawings he'd done and never showed me," Wyeth told me. "But I did an awful lot of drawings of him too, that's for sure."

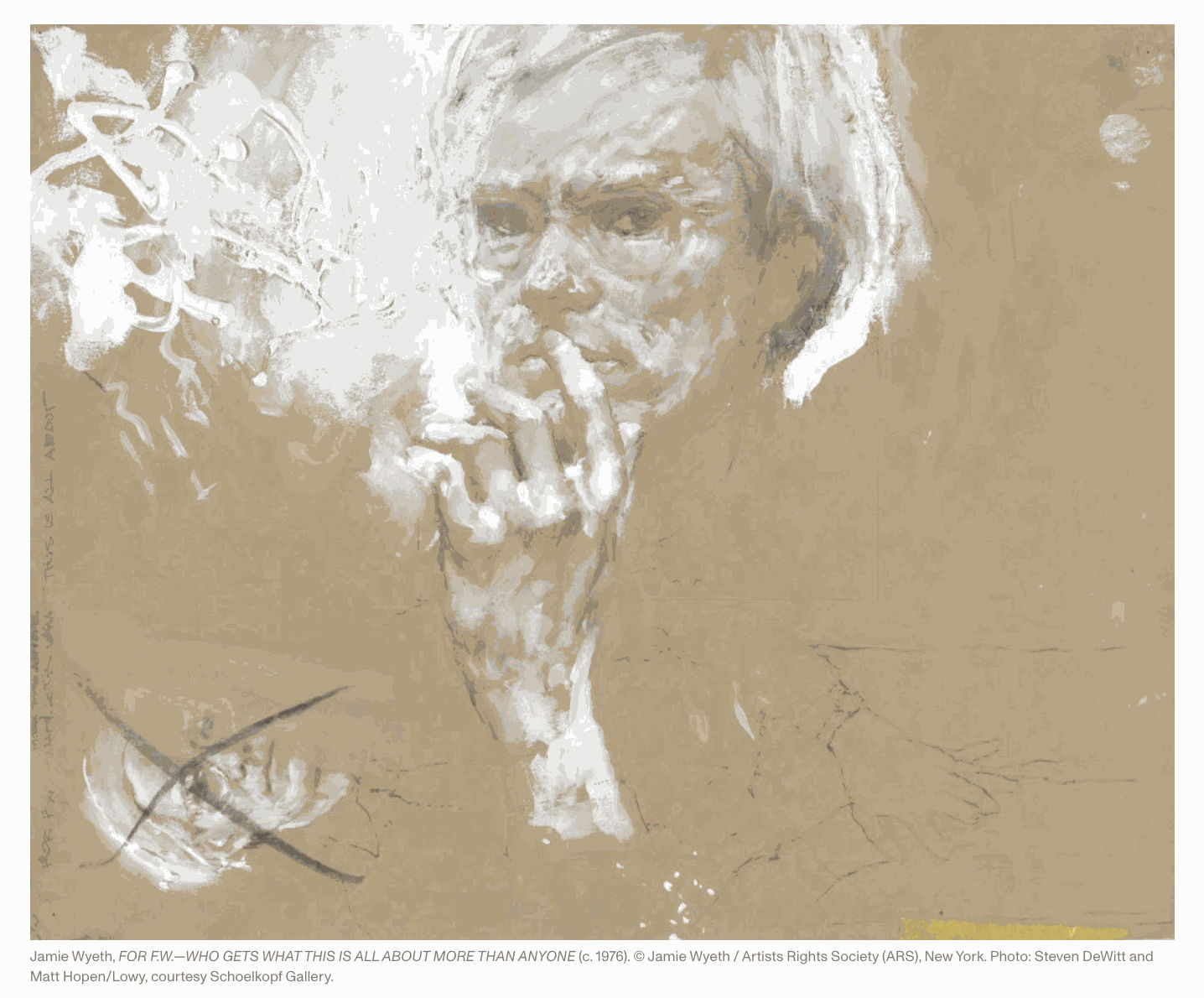

Next month, Wyeth is unveiling his own never-before-seen portraits and drawings of Warhol at Schoelkopf Gallery in New York. These works were collected and secreted by Wyeth's late wife, Phyllis Mills, not long after the joint exhibition. "I was working so steadily and hard that I had no idea what I was producing and where it was," Wyeth explained, adding that Mills had stored selected works because "I guess, she didn't want me to sell these." He stumbled on the cache two years after her death in 2019.

Seeing them after some 50 years, Wyeth was struck by Mills's choice of which pieces to stash away-"rather curious, unusual ones"-as much as what they lay bare. "Some are quite personal," he said, "and some are revealing of the person."

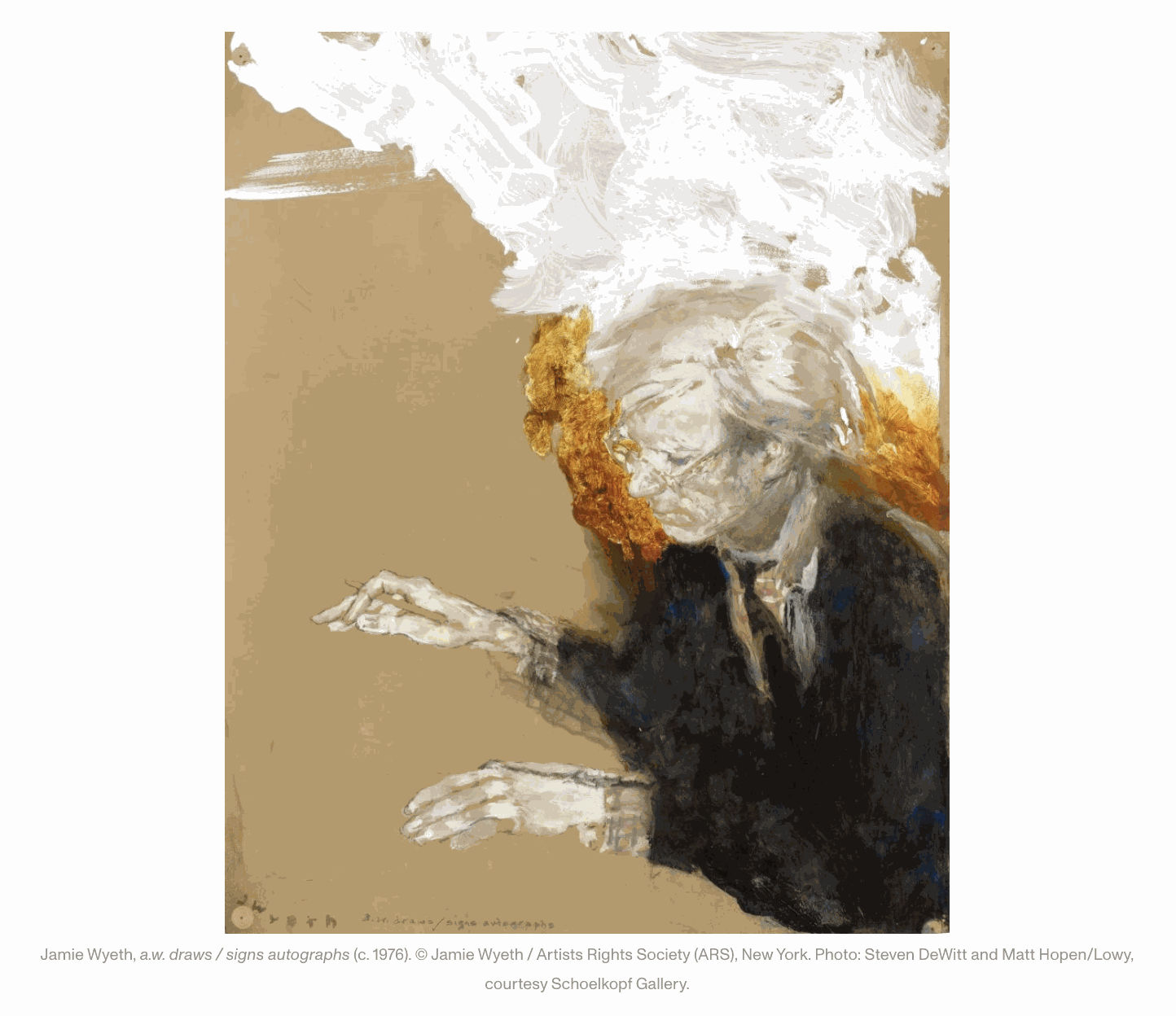

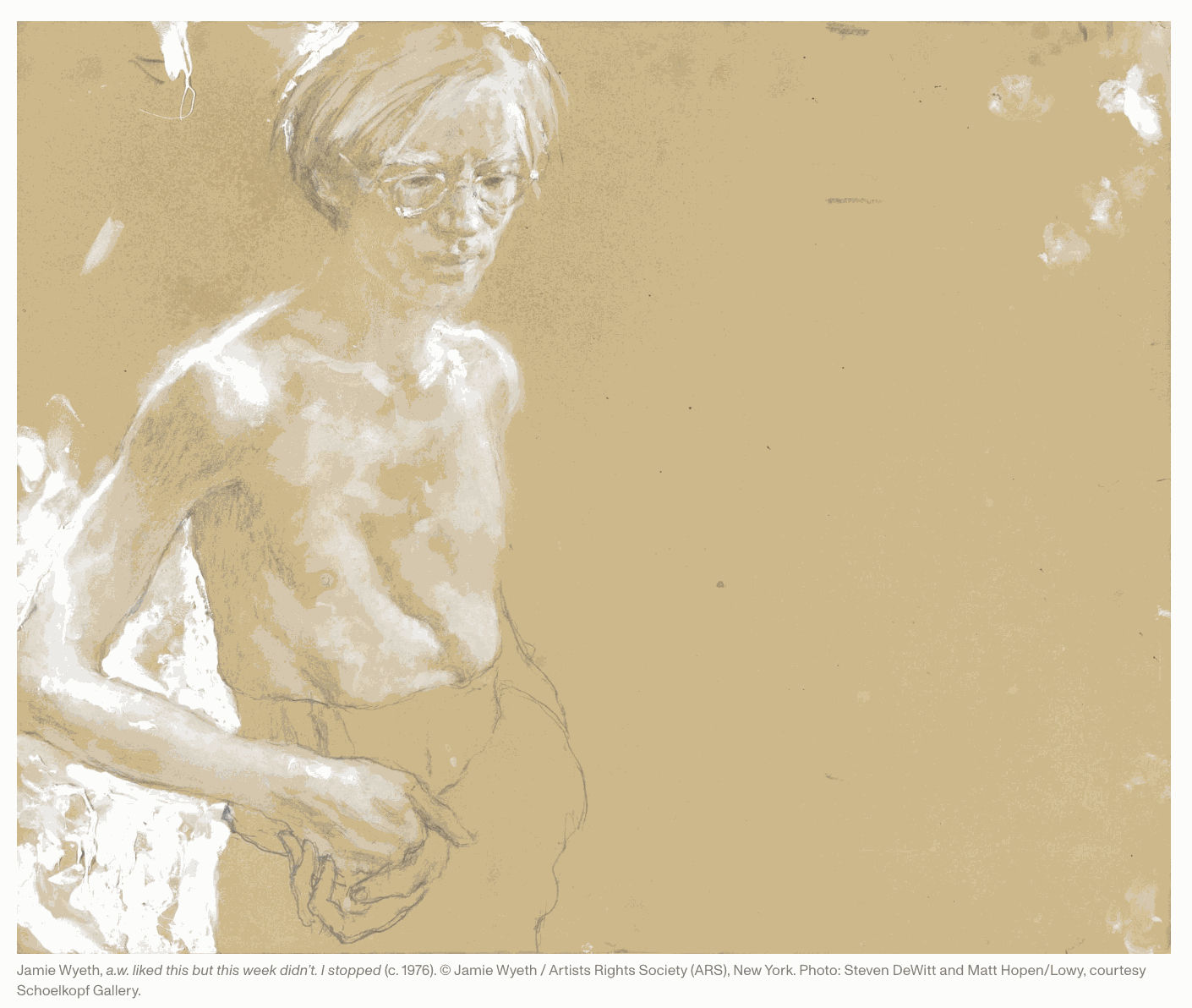

Wyeth's drawings of Warhol are indeed intimate and sensitive, shedding light on a man he deemed "extremely private." Where one captures the elusive artist deep in thought, his glance steely, another picture, titled a.w. III at ease, sees an unguarded Warhol as he holds Archie in his lap. In one more image, Warhol is shown shirtless, his thin frame bearing a scar from when he was shot in 1968; the work is tellingly titled a.w. liked this but this week didn't. I stopped.

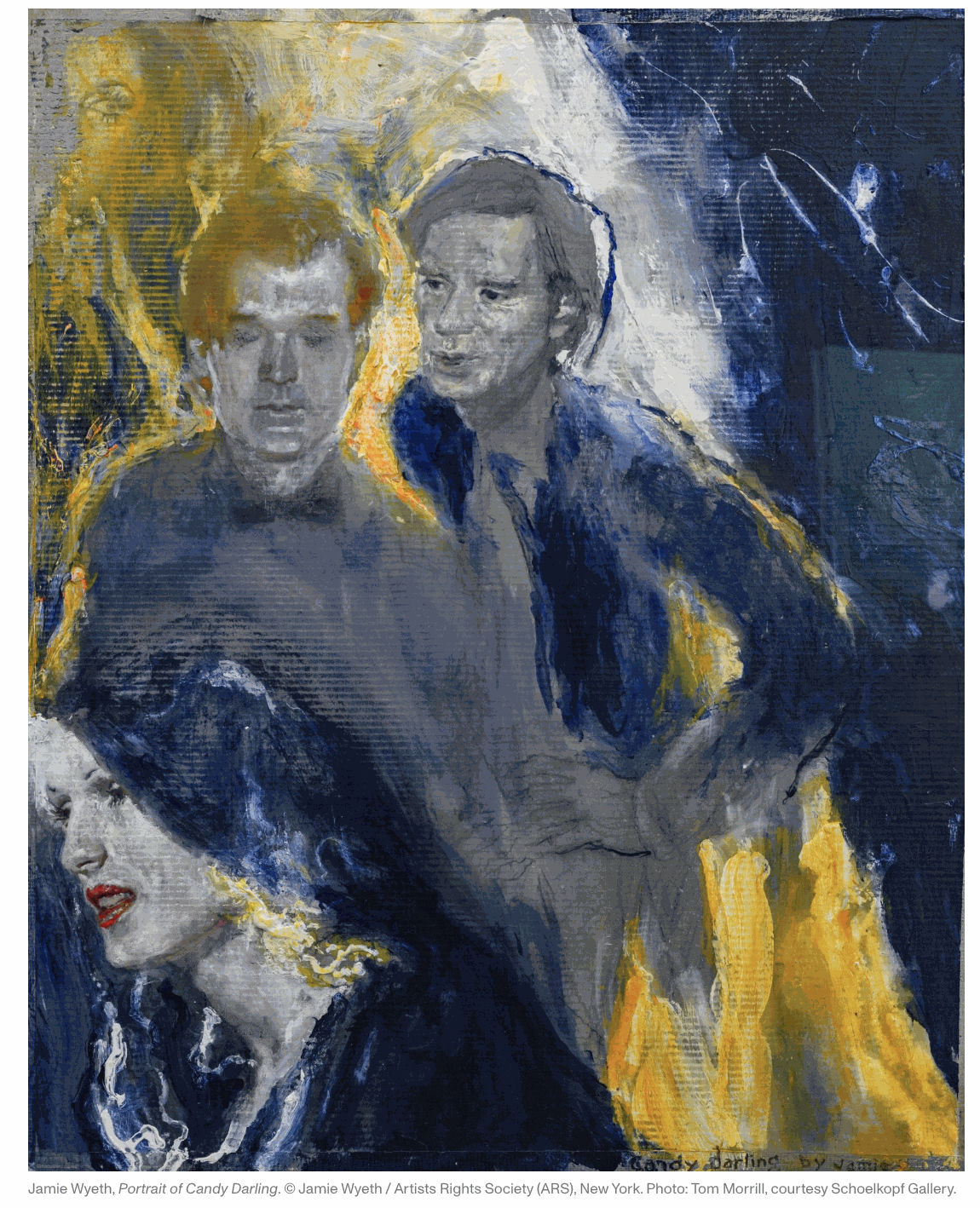

A further number of colorful canvases portray a Warhol in his element. He's seen tied up on the phone in a textured, cerise-toned piece, and depicted hanging out with Fred Hughes and Candy Darling in other similarly abstract compositions.

To gallerist Andrew Schoelkopf, Wyeth's drawings of Warhol almost carry a "journalistic quality," revealing his gifts as a draftsman and a storyteller.

"You can tell that he's just right there, and he and Warhol are just experiencing working together and interacting," he told me over the phone. "When he starts adding color, he's really building the energy and the emotion in them."

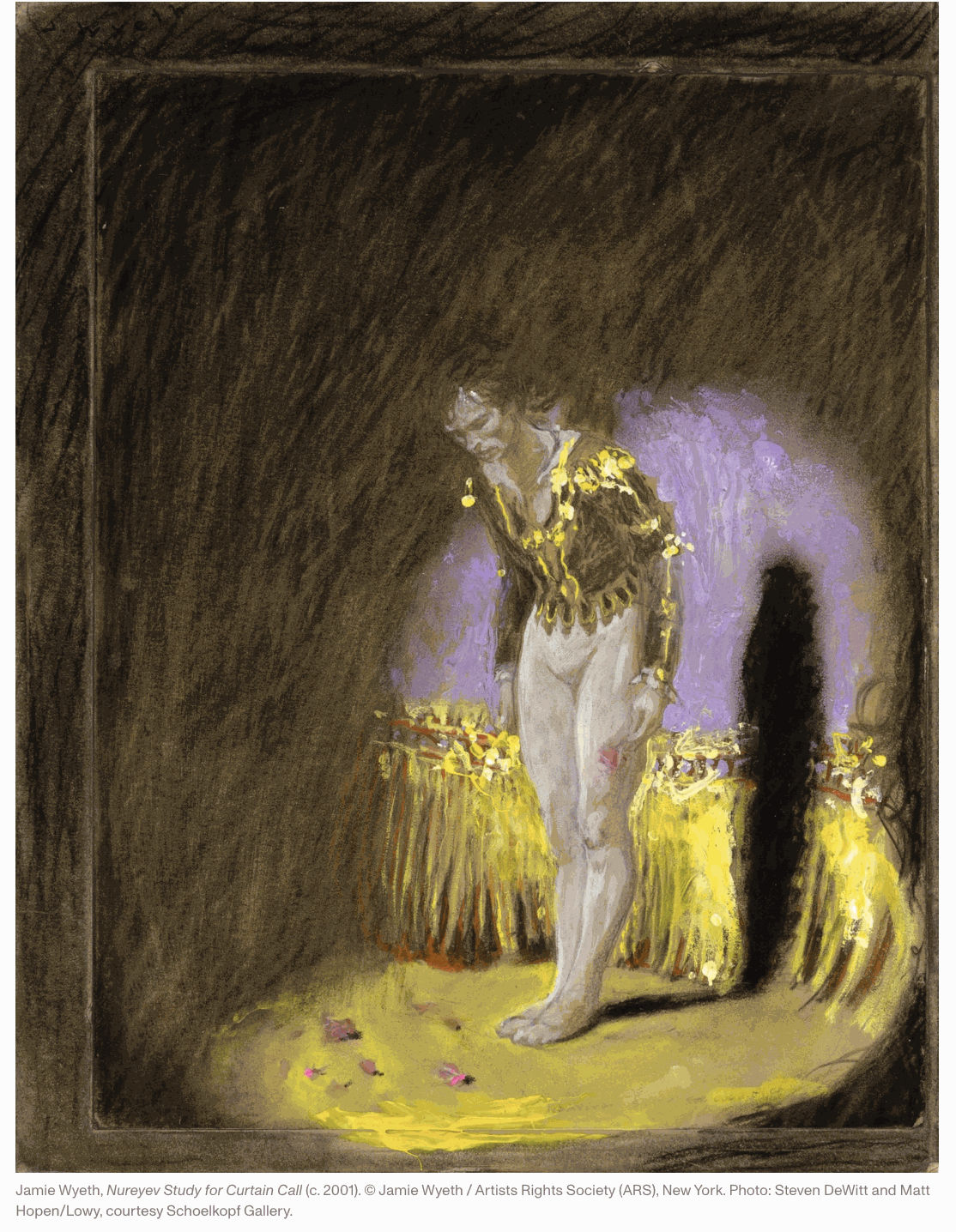

The newly unearthed group of artworks also includes some of the painter's long-hidden portraits and drawings of Rudolf Nureyev. Both Wyeth and Mills were captivated by the Soviet-born ballet star upon meeting him in 1974. She invited Nureyev to spend time on their Pennsylvania farm, while he accompanied the dancer for a year in a bid to capture his form and movement-"sort of an oxymoron," he conceded.

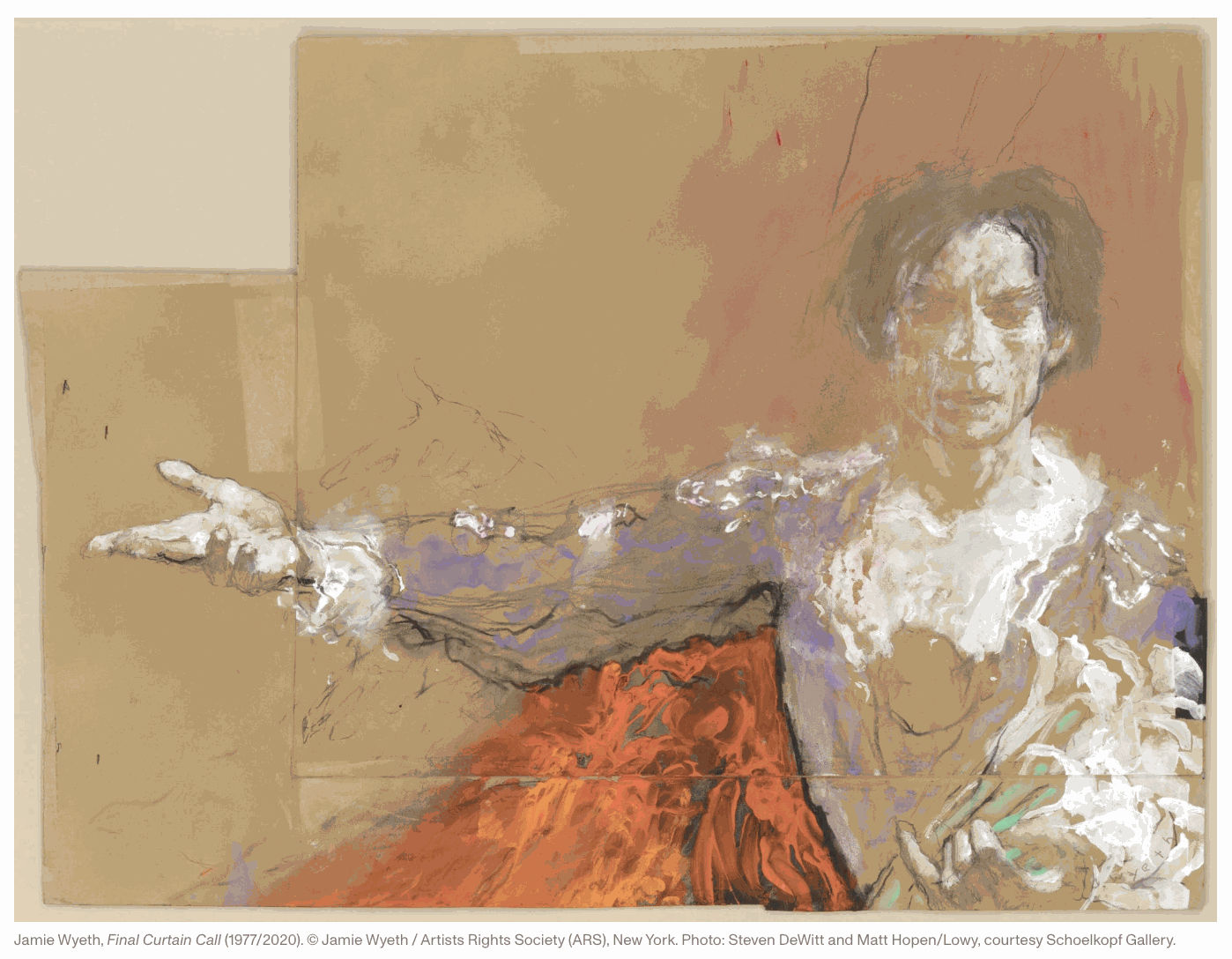

Still, Wyeth's compositions bear out Nureyev's phenomenal grace, physicality, and mystique. In one, he extends a hand in a dramatic gesture; in another, he appears poised with his arms splayed as if ready to leap. In a study for the 2001 painting, Curtain Call, Nureyev is seen mid-bow in a scene infused with pathos.

Other pieces depict the dancer in rare moments of stillness, such as a drawing titled One of the Few Times You Actually Posed for Me. According to the artist, Nureyev could be an exacting sitter: "I'd be drawing his foot or something, and he'd look over at the drawing and say, 'No! My foot more beautiful!' It was a lot of pressure."

Wyeth's own career was of course launched by a portrait: his posthumous image of John F. Kennedy, completed in 1967, when the painter was 21. It remains his most famous work (President Joe Biden borrowed it from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2021 to hang in his private study in the Oval Office). But, Schoelkopf pointed out, Wyeth's drawings of Warhol and Nureyev offer an even "better picture of the artist."

"Their creation, their rawness, and their immediacy are all so informative about the story and the experience Jamie was having with Warhol and Nureyev at the time," he said.

"There's so many sides," Wyeth said of portraiture. "And those two men, although entirely different human beings, were enthralling, just extraordinary."

"Jamie Wyeth: Portraits of Andy Warhol and Rudolf Nureyev" is on view at Schoelkopf Gallery, 390 Broadway, 3rd Floor, New York, September 12-October 17.