Mary Abbott was a quintessential uptown girl, replete with an immaculate New York pedigree that made her rise within the postwar downtown art scene and as a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism all the more intriguing.

Despite the significance of her work in helping to shape American art, Abbott’s legacy has been comparatively unsung, an all-too-common experience of women artists, particularly within the context of male-dominated AbEx. New York’s Schoelkopf Gallery seeks to correct this omission with “Mary Abbott: To Draw Imagination,” a comprehensive survey exhibition on Abbott—the first for the artist—which follows the gallery announcing representation of the artist’s estate.

“Given her upbringing and that she lived in New York all her life—she passed in 2019 and was working up through the very end—it’s surprising to know that she hasn’t had this big retrospective, or this big exhibition entirely devoted to her work yet,” said Schoelkopf Gallery Managing Director Alana Ricca. “But we’re working to correct that, and we hope that this will be the first of many.”

Born in 1921, Abbott grew up on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, attending the prestigious all-girls Chapin School. Her lineage can be traced back to both John Adams and John Quincy Adams, the second and sixth presidents of the United States, respectively. Her mother, Elisabeth Lee Grinnell, was a poet and syndicated Hearst columnist, and her father, Lieutenant Commander Henry Livermore Abbott, served in the War Department under Roosevelt.

Abbott showed an early interest in art, taking her first formal art classes at the Art Students League of New York at 12 years old. She would progress as a student there, later taking advanced classes under German artist George Grosz.

In 1940, Abbott was featured in Vogue advertising the season of debutantes and was later named “most glamorous debutante” by the Colony Club, where she made her own debut. She quickly became a name about town and worked sporadically as a model, appearing on the cover of Mademoiselle, Glamour, and Harper’s Bazaar.

Following a brief marriage to U.S. Army Airman Rudolph Clyde, coinciding with an even briefer stint out West, in 1946, Abbott settled back in New York, this time in Lower Manhattan in an apartment on Spring Street and rented a flat and studio in the East Village. She quickly became acquainted with fellow downtown artists, including Jackson Pollock, Grace Hartigan, and Elaine and Willem de Kooning, just to name a few.

Toward the end of the 1940s, Abbott enrolled at Subjects of the Artists, an experimental art school whose teachers included Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko. The experience marked a decisive turning point for both the development of Abbott’s work and her career. In 1950, her work was shown for the first time in the city at Kootz Gallery in “Fifteen Unknowns.” The following year she was included in the “9th Street Art Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture” also referred to as the “Ninth Street Show” at Stable Gallery, which is today regarded as the first formal exhibition of Abstract Expressionism, and included works by de Kooning, Pollock, Rothko, and Franz Kline. And in 1953, she was made a member of The Club, a multipurpose arts group and space that counted amongst a swathe of the city’s most influential artists and thinkers as members.

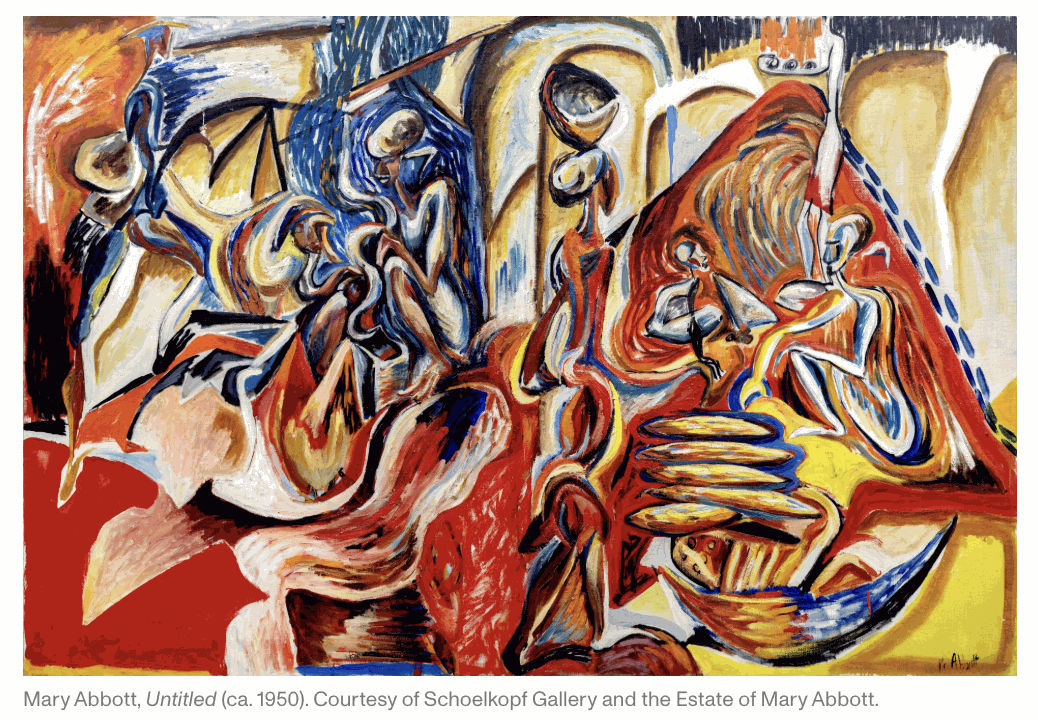

Some of the earliest works in “To Draw Imagination” hail from this period, including a vivid Untitled work from ca. 1950. Wrapped in churning tendrils of pigment, several abstracted figures can be distinguished amongst a disjointed, technicolor landscape. While figuration is rare in both the show and Abbott’s oeuvre, here it perhaps reflects another glamorous facet of the artist’s life.

In 1950, Abbott married Thomas Hill Clyde (whom she’d first met on St. Thomas while obtaining a divorce from Teague) in Southampton, and the couple spent the next eight years wintering at various locations in the Caribbean, including on Haiti and St. Croix (Abbott and Clyde continued to travel internationally over the following decades). On those travels, she completed sketches that she would later turn into oil paintings back in her home studio. The figures in Untitled echo the figuration seen in indigenous sculptures found in these locales, more specifically that of the Taíno art, which she would have conceivably come across during one of her stays, and illustrate an early interrogation of the boundary between abstraction and figuration.

Another, slightly later Untitled work from approximately 1952 is exemplary of the artistic zeitgeist of the time. Swathes of muted color are punctuated by vibrant patches and scribbles of color and gestural lines, with every point of the canvas seeming to catch and carry the eye to another point, ceaselessly moving. While the influences of her teachers like Rothko and Motherwell, or even de Kooning can be discerned, her style simultaneously resists easy attribution. Its expressiveness points to Abbott homing in on her own, distinct personal expressive method.

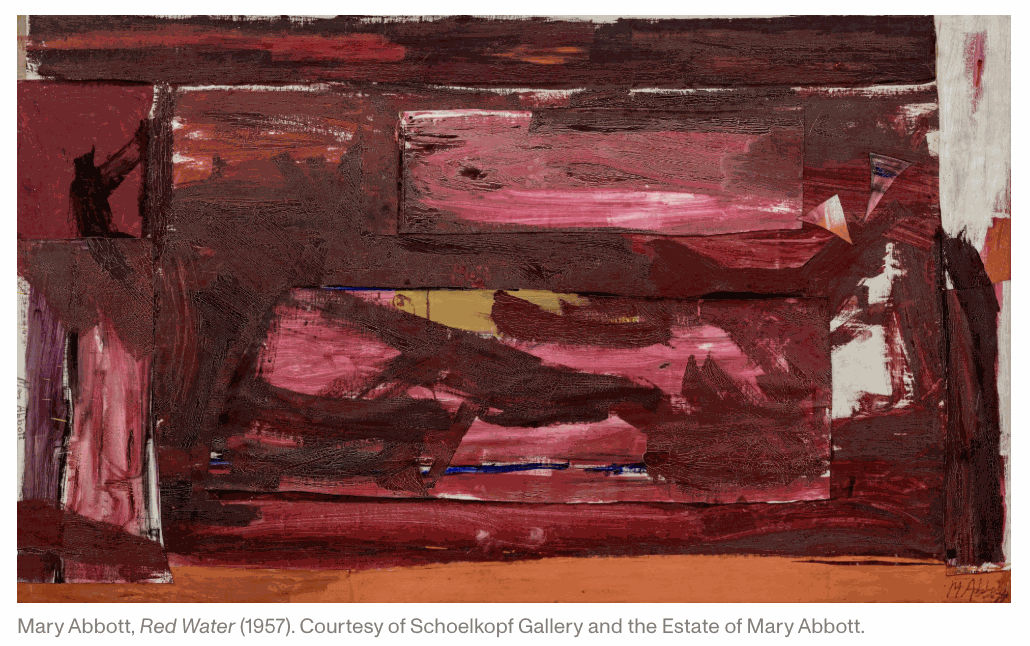

Work from the later 1950s highlight Abbott’s fearlessness towards experimentation. Red Water (1957), one of the few formally titled and dated works, comprises several complete paintings that have been cut and collaged together. The exuberant composition of overlapping and gradating expanses of color is lavish in its structure; it would seem Abbott didn’t hold her work or materials as precious, but instead as sites for rigorous creative work. The canvas has been signed on two sides, suggesting it could be hung either way, and at the very center of the piece on one of the cut canvas strips are two dog prints, indexical of the former painting that having been left on the ground where one of her beloved dogs stepped on it.

Her work from the 1950s visually parallels the developments within AbEx, and, unlike many of her contemporaries, showcases an intense preoccupation with the limits of artmaking itself, a theme which, broadly speaking, defined the development of 20th-century art on the whole.

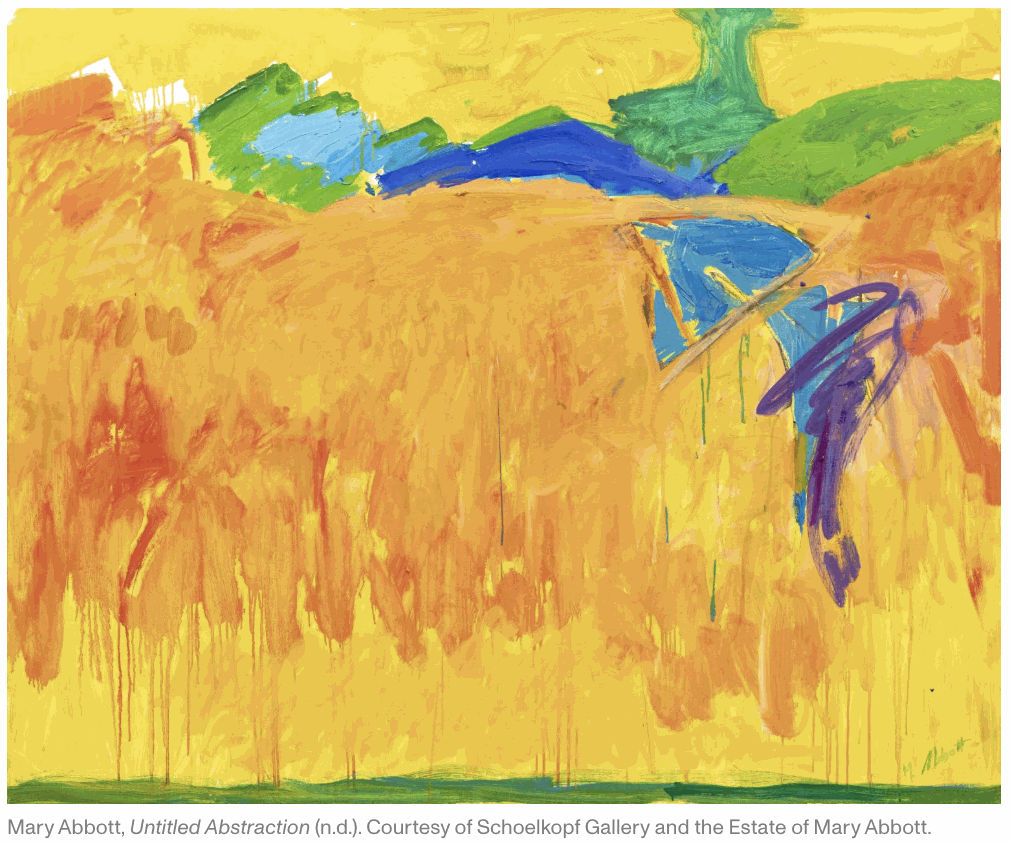

Examples of works from the 1980s show a return to elements of representation, albeit tempered with the language of abstraction Abbott had mastered over the decades prior. Living on Long Island, Abbott immersed herself in nature and found it a potent source of inspiration. Palm Frond, though undated, likely hails from this period and displays expressionist brushwork but a more careful approach to arrangement and elements of perspective.

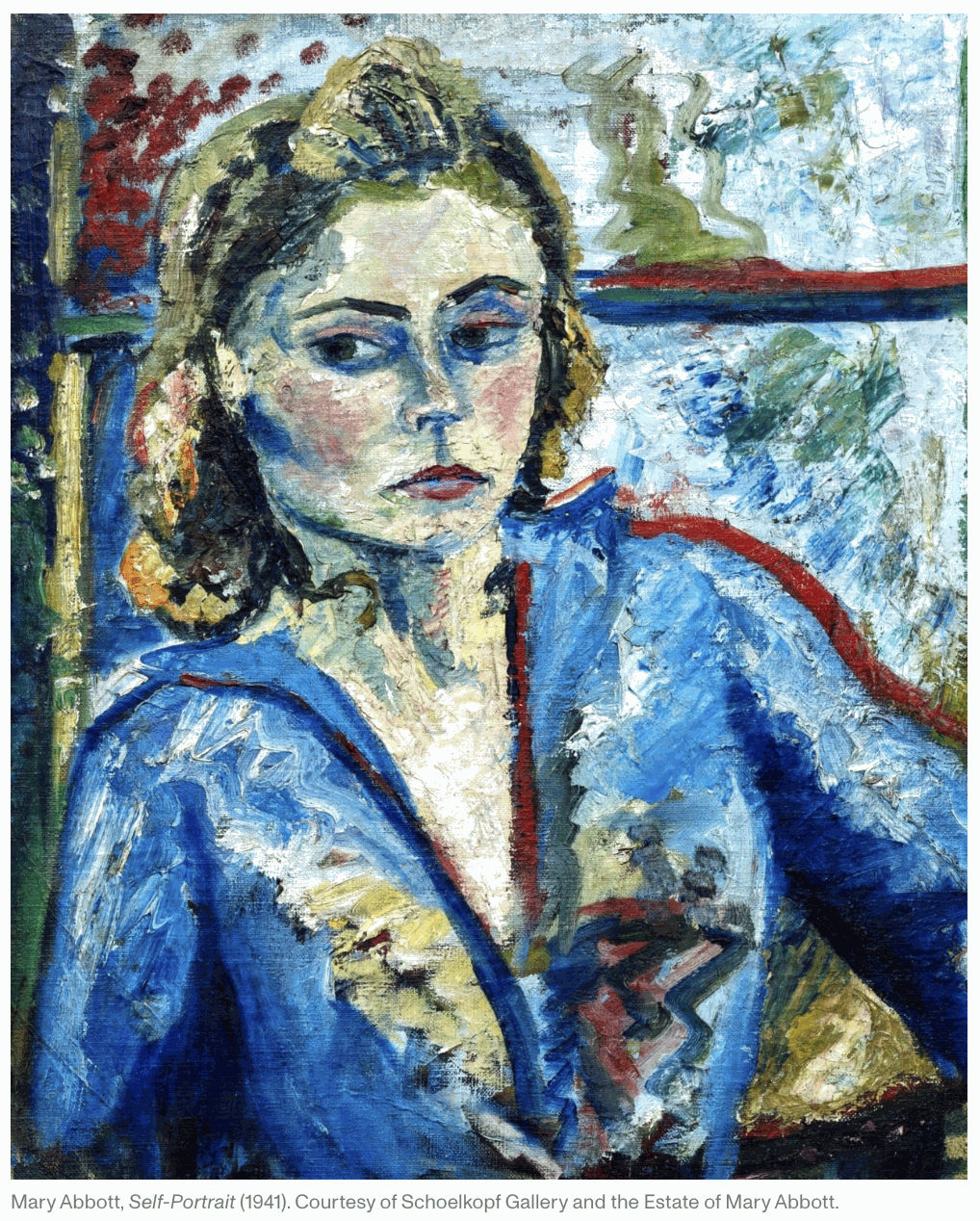

While the show features pieces dating through to the aughts, two self-portraits act as cogent “bookends” for the show: Self-Portrait (1941) and Untitled (Self-Portrait) (ca. 1980–89). The former shows the artist as a young woman, and while her face is stoic, the rendering of the overall composition alludes to what might be described as self-conscious. Where colors end or meet is rather stilted, and bold additions of contrasting hues appear almost forced.

In contrast to the 1941 work, Abbott’s mastery of her medium is on full display in Untitled (Self-Portrait), created roughly four decades later. Reminiscent of Cubism and Surrealism in the rendering of her face, which appears to morph and meld with the blooming lilies, the ground is solidly an homage to her foundations in AbEx, featuring nuanced fields of gestural color.

Without relying on didacticism, “Mary Abbott: To Draw Imagination” conveys through carefully selected works from across the entirety of Abbott’s body of work the multi-decade evolution of her practice. No period of her life or practice was static, and in the same manner, neither was her work. Abbott remained in unyielding pursuit of the possibilities of her medium, which can be traced canvas to canvas.