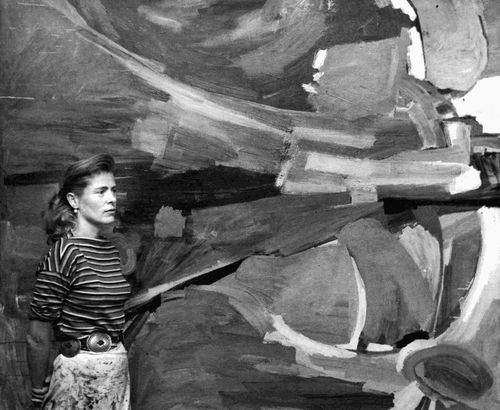

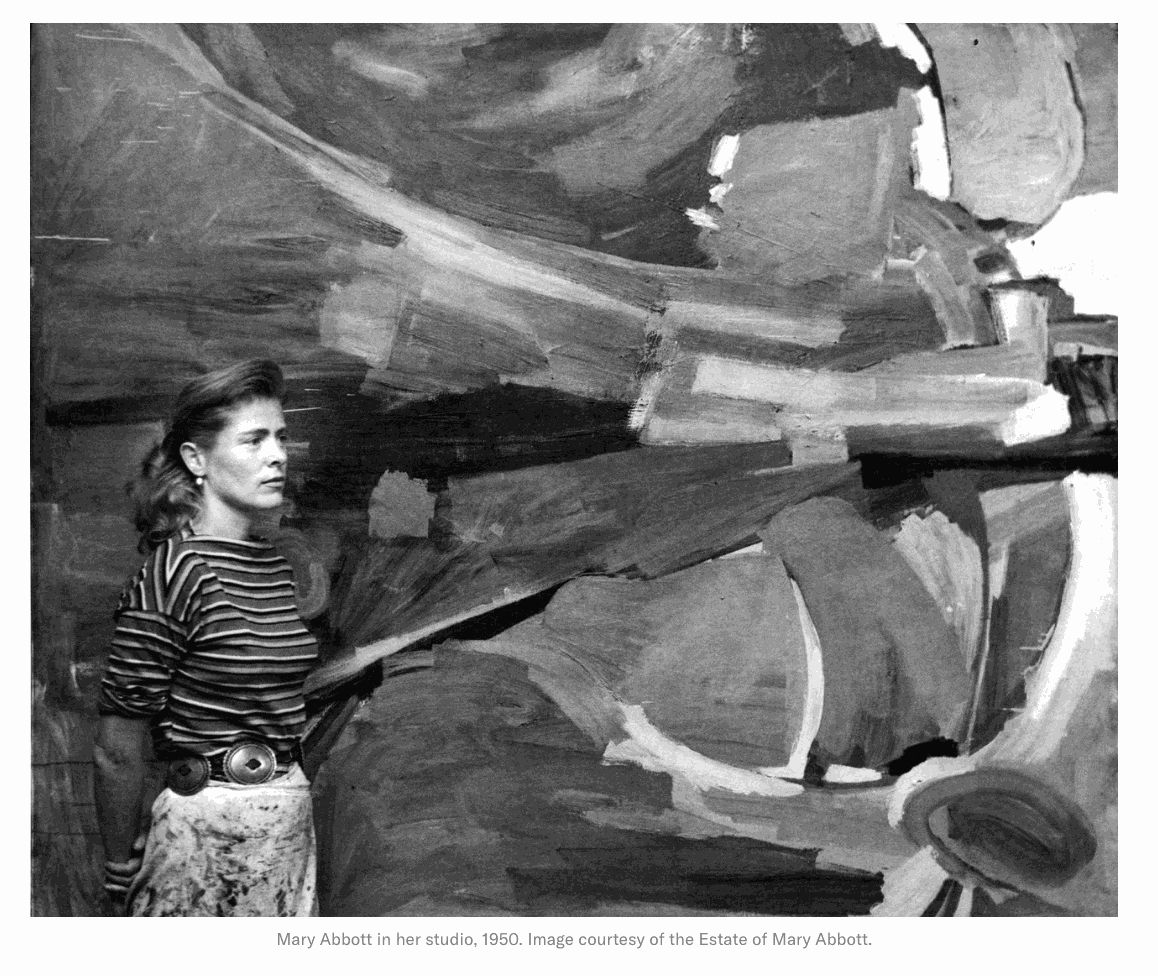

Before she studied under Mark Rothko, or painted alongside Willem de Kooning, Mary Abbott was already a fixture of New York’s cultural scene. Born in 1921 to a family that traces its roots to Presidents John and John Quincy Adams, and raised among poets, sculptors, and diplomats, she seemed destined for a life of refinement—not rebellion. Vogue featured her in a spread advertising the 1940-41 season's debutantes, where she was ultimately named the “most glamorous debutante,” but soon, she left the Upper East Side behind to dive headfirst into the bohemian swirl of postwar downtown Manhattan.

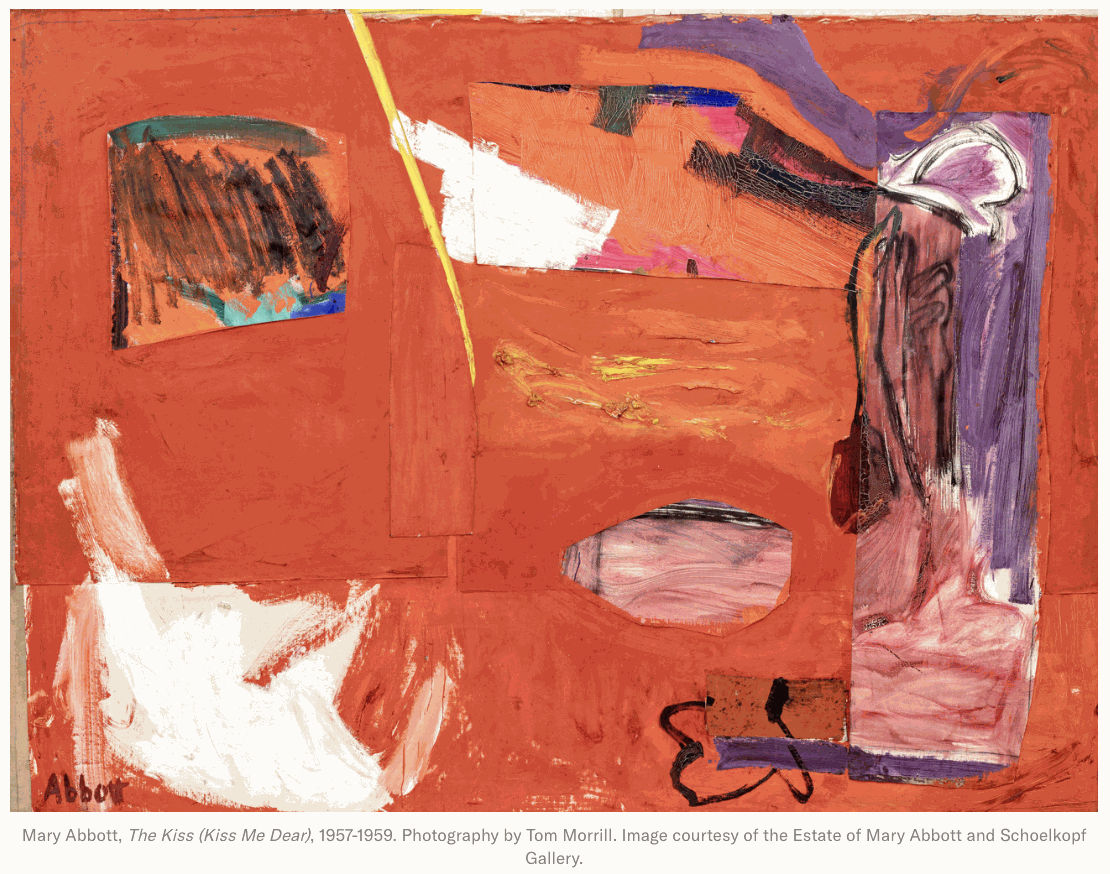

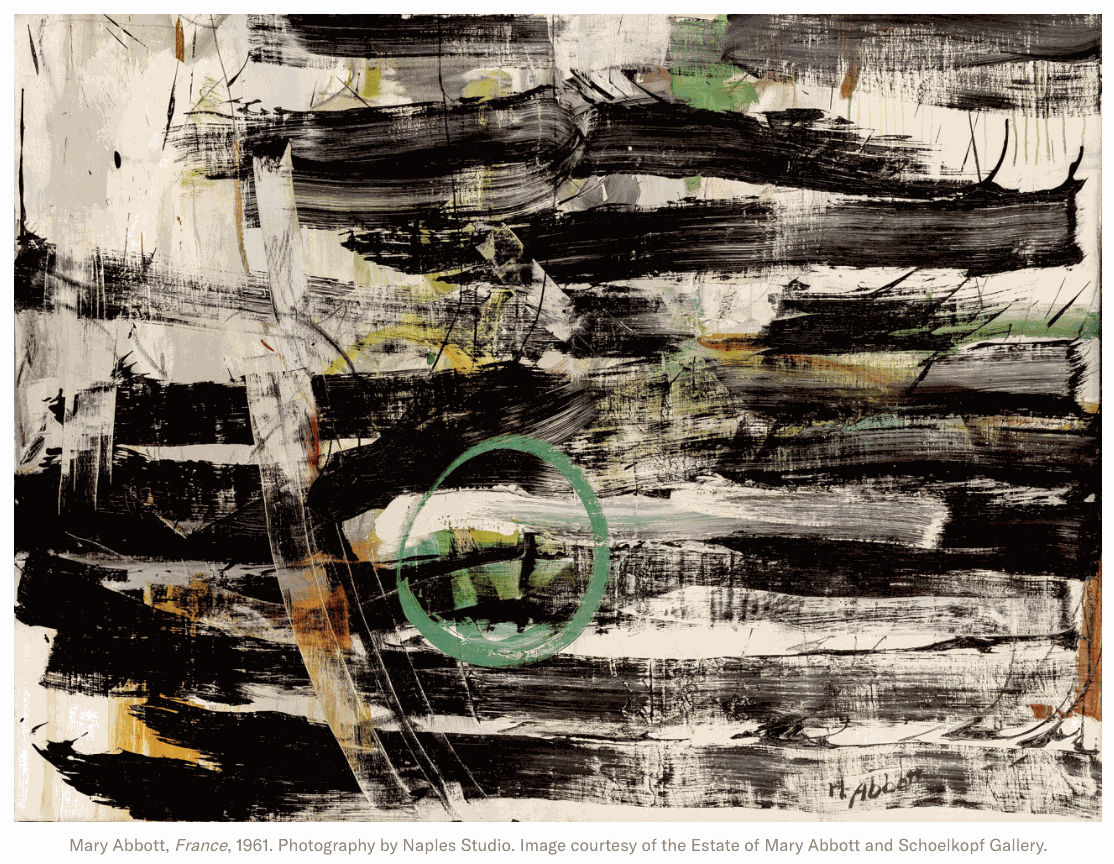

Though the late artist's contributions have been oft overlooked in favor of the male titans that were her contemporaries, “Mary Abbott: To Draw Imagination,” opening May 9 at New York's Schoelkopf Gallery, illuminates her place in the Abstract Expressionist canon. “It’s taken years for the establishment to embrace her contributions,” says the gallery's managing director, Alana Ricca. “We are now in a very rich moment of reconsideration for artists that hadn’t achieved the same level of critical acclaim as certain of their peers.” Spanning six decades and over 60 pieces, the first retrospective of Abbott's work charts the sheer breadth of her practice, from her early Surrealism-influenced drawings to her explosive mid-century canvases and experimental late-career works on paper. Rarely seen pieces from her estate showcase her material versatility—oil, charcoal, pastel, and collage are all rendered with an intuitive hand.

A muse to many but a follower of none, Abbott’s work expanded Abstract Expressionism’s gestural vocabulary with color-driven lyricism, tactile experimentation, and a reverence for nature. Her paintings, often completed on her holidays in the Caribbean or at her studio in the Hamptons, pulse with sensual immediacy. The show’s title borrows from Abbott’s own words on Rothko and Barnett Newman, whom she said “taught us to draw imagination”—a mantra she embodied as both an artist and, later in life, educator. “It’s increasingly rare to look at an artist’s entire body of work that, for the most part, hasn’t been seen before by the public,” remarks Ricca. “Often times in putting together an exhibition of this scale, we’re struck by individual moments or works that really stand out. For Abbott, it was the enormity of her talent that was so in harmony with the incredible life she led.”

Abbott moved easily among the luminaries of the New York School and was one of few women admitted to the Club—a member's only, male-dominated hub of Abstract Expressionist thought. However, she often missed era-defining exhibitions—not for lack of talent, but because she was abroad, painting. Recent international shows, from “Women of Abstract Expressionism” in Germany to “Action / Gesture / Paint” in England, have reignited interest in her singular vision. A catalogue with essays by Gwen Chanzit and Laura Smith accompanies Schoelkopf's exhibition, fully fleshing out Abbott’s legacy as a restless artist with poetic force.

“Her life informed her art in so many ways,” says Ricca. “She graced the pages of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar in her early years, but rented a cold-water flat on 10th Street, dedicated herself to a life of making art, and pursued a relentless exploration of the world. What really emerged, to me, was her constant experimentation with new media, techniques, and forms that paralleled her passion for life.”

Schoelkopf Gallery's "To Draw Imagination" is on view May 9 through June 28, 2025 at 390 Broadway, 3rd Floor, in New York.