Clifford Ross: What Remains…

Jock Reynolds’s 2015 essay “Natural Encounters” observes that Clifford Ross first began engaging with “the belief that representational imagery did not need to wage an irreconcilable war with abstraction, but the two could in fact exist side by side, in creative tension” with his “Hurricane Waves” photographs. Ross inaugurated this series in 1996, donning a wetsuit to enter storm-shaken, writhing waves, securing himself to the nearby bay to photograph the milk-like foam and its alabaster spray crash. If abstraction is espied in these images, it is the result of close-up angles that offer unfamiliar, alien glances rather than the illegibility of natural forms. So captured, wave crests appear to fold into one another, undulating and lapsing into angular manifolds.

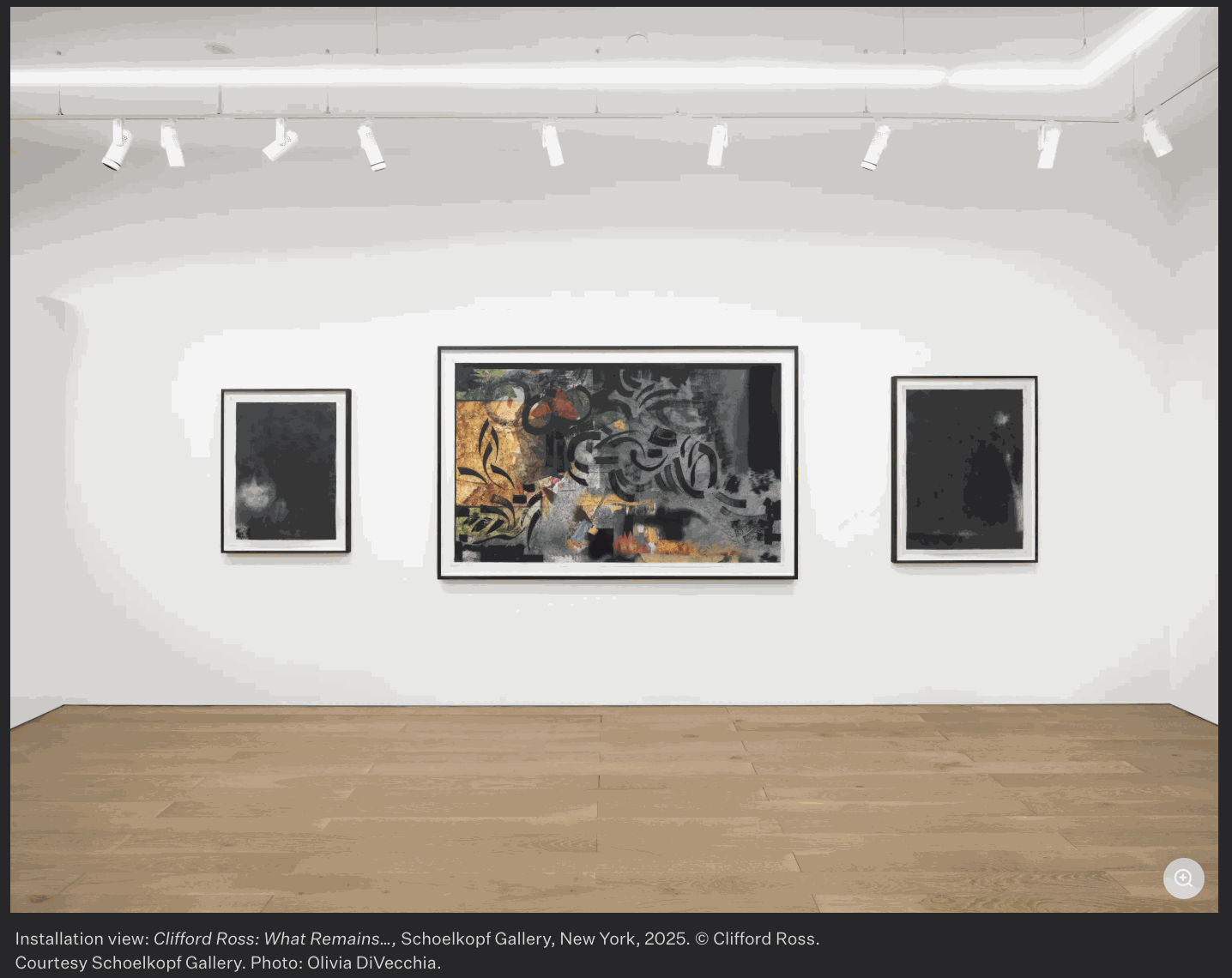

Perhaps this intimated one form of abstraction, but it is not exactly the kind of abstraction at play in Ross's What Remains… at Schoelkopf Gallery. The exhibition includes twenty-four works from various series executed in 2020 and 2021. Throughout, abstraction becomes a graphite afflatus that whisks, overtakes, and swallows photographic imagery. Many of Ross’s works revisit the modes of abstraction that he has turned and returned to throughout his career. To repeat Reynolds’s turn of phrase, abstraction is set into “creative tension” with “representational imagery” as Ross charts marks and blemishes across colorful diamond- and parallelogram-shaped shards.

The variegated, parceled folds that make up the scattered backgrounds of Ross’s “Nicolette and the Blackbird” and “Postcard From the Volcano” series (both 2021) are photographs that will be familiar to viewers acquainted with Ross’s antecedent Velvet Cloud (2008) and Harmonium Mountain (2010) imagery—viz., high-resolution photographs of Mount Sopris translated into three-dimensional, computer-generated elements. Layered into laminate mosaics, these representational indices of the natural world are literally and figuratively abstracted, overtaken and all but erased by gestural, hoary graphite whirls such that, whatever worldly information the background images might signify is rendered non-notational. These works are, in turn, doubly self-effacing.

In the graphite and ink Blackbird (2021), an irregular quivering of light is dotted with flecks of ore-black sandy grains and a burst of kaleidoscopic shards. In A Death Left Incomplete I and II (both 2021), similar dots are coalesced into a foaming white wave, attesting to the shared source imagery between Ross’s mark-making and his digitally enlarged photographic imagery of crags, mountains, and hurricane-tossed waves. The images that belong to the latter set make up much of Ross’s background imagery but, when digitally amplified, they bear little resemblance to their empirical sources. Here, Ross manipulates the natural-empirical world into one rife with abstractions invisible to the everyday eye, where his abstracting amounts to digitally selecting a mark suited for a subjective purpose. What, then, is Ross’s purpose?

This is not an altogether easy query to answer. When, famously, Ross developed his R1 camera in 2002, he was motivated by capturing mountainscapes with exacting verisimilitude, hoping that the percipients of his high-resolution images might be able to enjoy what Ross deemed the “reality quotient” and “you are there” quality of viewing such natural landscapes in person. But why, then, has Ross—the artist-photographer renowned for his commanding realism—done away with perceptual acuity in his recent works, collapsing the landscapes into pixelated digital flickering? One answer, perhaps, has to do with the likenesses that remain as Ross zooms in on a photographed natural image. This includes the homology that obtains between the monochromatic foam spatters of his “Hurricane” series’ wave crests and the ethereal, dot-ridden adumbral forms culled in Blackbird and related luminous works, including The Blackbird Whistling or Just After II (2021) and What Remains I (2021). In light of Ross’s earlier photography, one can not help but interpret his latter works’ marks as frothed spray. Sifting the natural world’s indices by way of digital enlargement, Ross remains resolute in his thorough-going Romantic insistence that the wilderness continues to suggest (but only suggest) itself.

In his entirely beclouded graphite works like What Remains II (2021) and Conversation With a Silent Man, Ross stages a march backward in biographical time. In the 1970s, when Ross initiated his fine art career, he executed color fields inspired by the post-painterly abstraction of Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, and Jules Olitski. Admittedly, in his newer works, irregular and slight breakages score Ross’s powdery steel-gray strokes, indicating that works like Conversation are by no means depictions of flat fields, proper. But the oxidization effect is relatively similar to the lexicon Frankenthaler employed in works like her thinned-down “soak-stain” painting, Canal (1963).

It is at the midpoint between the calligraphically decorated Postcard From the Volcano I and the all-over blemished Conversation With a Silent Man where Ross’s recent work most strikingly balances beauty with conceptual riches. That is, the most compelling works on display, neither purpose the naturalistic background imagery with ornamental marks nor fully occlude it. This is why Ross’s “Nicolette and the Blackbird” series is particularly successful. Silvery stygian eruptions swing from the upper-right edge of the canvas, overtaking glowing red shards and verdant parcels before swallowing the bottom edge of the picture plane whole. Here, Ross’s effacing strokes are made purposive, rolling in and out of his photographic imagery, thereby highlighting it. Rather than being self-serving, Ross’s abstraction is here set into a genuinely “creative tension” with the figurative fragments that it subtends.