By Julie Davich, January 19, 2025

Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall decided to sell their collection six months before fires ravaged Los Angeles. Now, dozens of 20th century works are safe, sound, and for sale in Tribeca.

About six months ago, Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy and her husband, the film producer Frank Marshall, made a prescient call to their art advisor, Barbara Guggenheim. The couple, who live in Sullivan Canyon in Brentwood, were nervous about the risk of wildfires and wanted to sell the collection of 20th century American regionalist and social realist art that they’d built over nearly four decades.

Guggenheim—who first met the couple in the ’80s, when they were working with Steven Spielberg and George Lucas on E.T. and the Indiana Jones movies—was determined to see the works presented in a cohesive way that honored the couple’s vision. The result is American Stories: The Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall Collection, an exhibition (and accompanying catalogue) on view at New York dealer Andrew Schoelkopf’s Tribeca gallery through February 28.

The show arrives amid an undeniably complex moment in Los Angeles. Kennedy and Marshall’s home was spared from the fires, and yet so many others were destroyed, likely including the loss of a good deal of art, too. Meanwhile, if you’ve been reading my partner Matt Belloni, you know Kennedy’s role as the head of Disney-owned Lucasfilm has long been the subject of industry gripes and conjecture that her position is untenable. None of this would be particularly jarring to Guggenheim, the widow of hard-nosed entertainment attorney Bert Fields, and someone who has counted Lucas and Tom Cruise as clients.

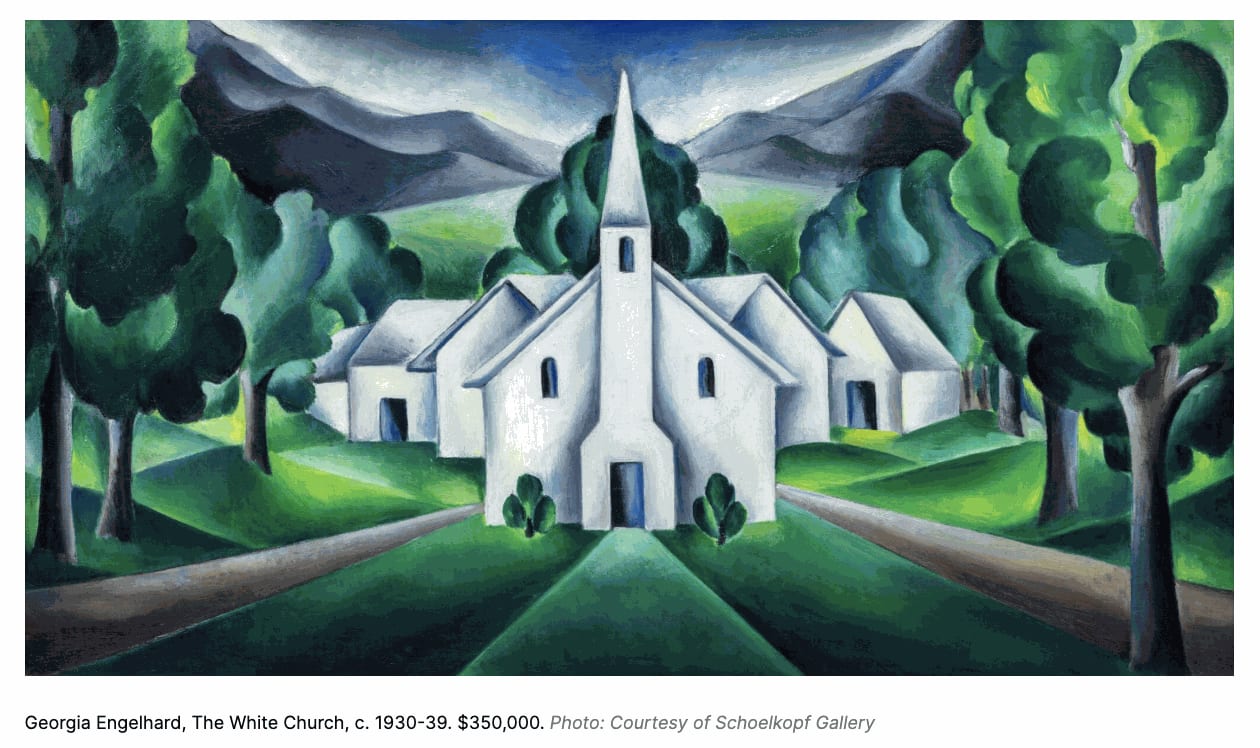

When Guggenheim first started working with Kennedy and Marshall, she landed on the idea of “narrative art” as a guiding principle—a theme that she believed would resonate with the filmmaking couple. The collection consists of 39 works by artists whom Guggenheim described as “socially responsible storytellers.” There are strong examples by Romare Bearden, Thomas Hart Benton, Jacob Lawrence, and Ben Shahn, as well as important works by less well-known artists including Georgia Engelhard, Jared French, and Paul Sample.

There’s been an uptick in the market for American modernism, which Schoelkopf managing director Alana Ricca attributes to two factors. First, there has been an increase in international demand for these works from the U.K., continental Europe, Japan, and South Korea, along with some early interest from the Middle East. And second, collectors are starting to see these works as precursors to American postwar art and want to round out their holdings in that category. Already, 15 works from the collection have sold, including the most expensive: a large Bearden collage from 1968 priced at $900,000.

Social Realist Steals

While touring the gallery together, Ricca steered me to a 1930-39 painting of a white church by Engelhard, who was Alfred Stieglitz’s niece, available for $350,000. Engelhard spent only a short amount of time painting before famously turning to mountain climbing—becoming the first woman to ascend many of the tallest peaks in the Rockies—so there are few examples of her work in existence. She started this particular painting when she was very close with Stieglitz’s wife, Georgia O’Keeffe, and you can see the older artist’s influence, especially in the shading. For any collector who is priced out of the O’Keeffe market—which has never been higher than at this moment—the Engelhard work is a steal.