Stuart Davis American, 1892-1964

61 x 81.3 cm

Davis was putting the finishing touches on Memo No. 2 when Jackson Pollock was killed in a car crash in the late summer of 1956. The two painters were considered among the most important artists of their time and had been anointed as such by the popular press. Life magazine had proposed Pollock as “the greatest living painter in the United States” in 1949. The previous year, Look had conducted a poll of forty art critics and museum professionals to identify “the Best Painters in America Today;” Davis came in fourth, behind John Marin, Max Weber, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. [1] Pollock and Davis were, in effect, the standard-bearers for the two competing forms of abstraction prevalent in the United States in the 1950s: subjective, spontaneous, and inward-looking vs. objective, rational, and based on the external world.

It is not clear what Pollock thought of Davis, who was twenty years his senior and on the faculty of the Art Students League when Pollock was a student there. [2] For his part, Davis had long distrusted Expressionism of any kind, including Abstract Expressionism, because of its “denial of the objective world,” its rejection of his deeply held belief that art must be based on concrete experience. “Any kind of painting is always a likeness of something,” he said. [3] Nonetheless, he found much to admire in Pollock’s work, describing Pollock’s pictures from 1950–51 as “the most direct and uncluttered specimens of the essential content” and in a 1952 radio broadcast calling Pollock and Willem de Kooning significant American painters. [4] He made a point of visiting the memorial exhibition for Pollock held in December 1956 at the Museum of Modern Art, commenting that Pollock’s work “has Art quality . . . arrived at the hard way.” [5]

Memo No. 2 made its debut at the Downtown Gallery in November 1956, a month before the Pollock memorial exhibition. It was Davis’s first solo show in two and one-half years and included fourteen paintings, most of them made in 1955 or 1956 and fully representative of what would come to be seen as his late style. A number of paintings were sold out of the show, or even before it opened, some of those to museums. [6] Among them was Ready to Wear (1955), which the Art Institute of Chicago purchased for the gratifying price of $6750. Memo No. 2 was bought by the Iowa retailer and noted art collector James Schramm a little more than a year after the exhibition closed.

Critics were enthusiastic. Stuart Preston, writing for the New York Times, called the paintings “as boisterously abstract as any he has ever done. . .. [They present an] intricate and ambiguous dance of his tough-minded shapes and vociferous color.” Hilton Kramer, in Arts Magazine, praised Davis’s “modernized. . .realism” that “face[s] up to the bright new vulgarities of our mechanistic civilization. [Davis] substituted for the realism of his elders a montage-like abstraction which derived its components from the urban life around him but which were now, under the dispensations of modernism, purified and re-designed to form a more direct plastic equivalent of the local emotion he was trying to convey.” [7]

These sobersided analytic reviews convey the high esteem in which Davis’s work of the fifties was held, but miss its humor and energy. A more rounded—and, appropriately, more amusing—assessment of Davis’s late style came from the painter and critic Brian O’Doherty, who characterized those works as “paintings of the honk and jiggle. . .canvases that blare, burp, and hop with bright, shallow color.” [8]

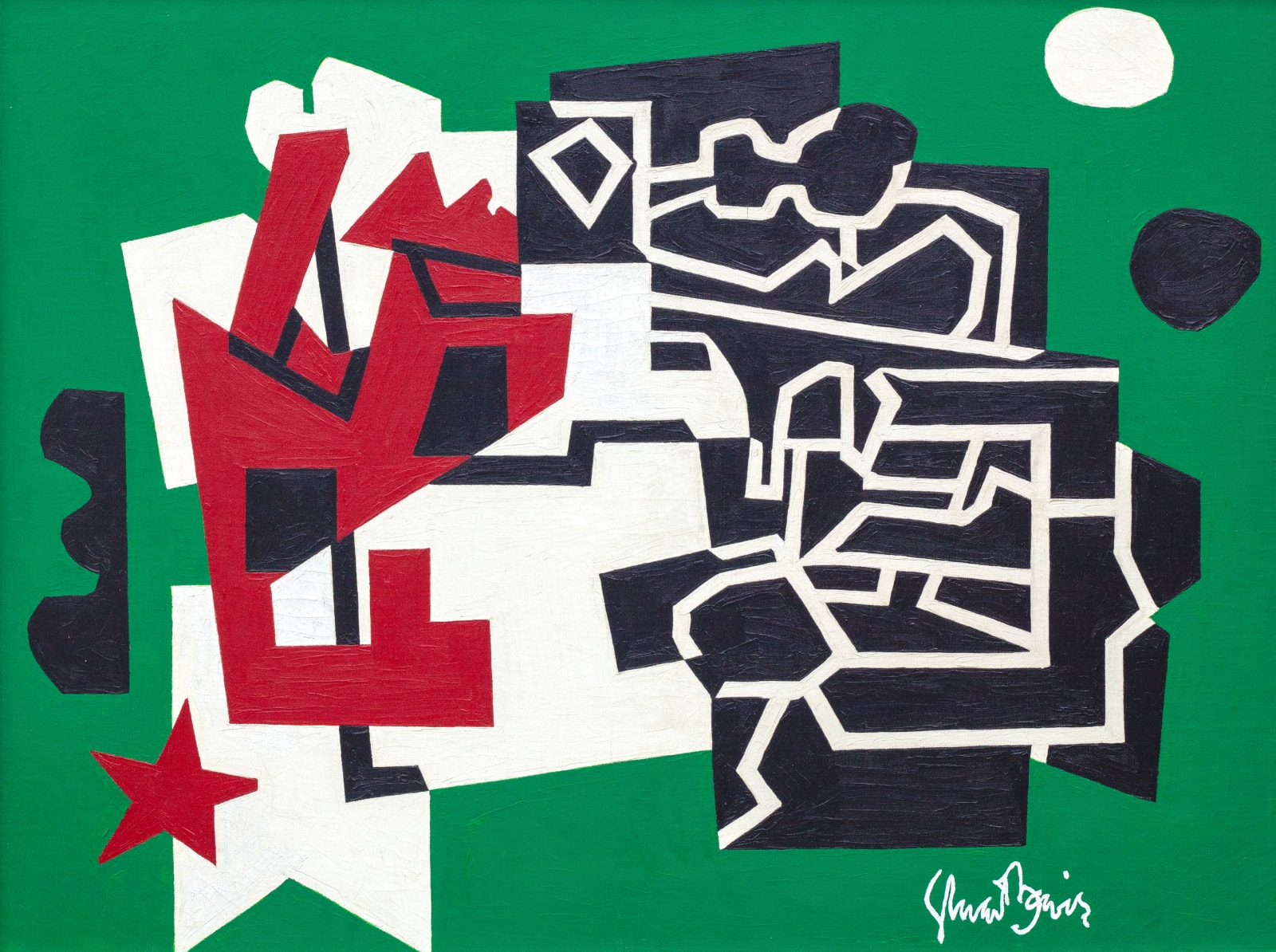

Memo No. 2 certainly honks and jiggles, burps and hops, but it is at the same time carefully structured. The painting consists of two balanced halves, white lines against black and black and red shapes against white, with a red star in the lower left corner pinning those blaring shapes to a flat green ground, a small element that somehow holds everything in place. This split-screen approach was one of Davis’s favorite compositional devices, going back to House and Street (Whitney Museum of American Art) of 1931, or some of the “Egg Beater” pictures of 1928. The silhouette of shapes in Memo No. 2 has antecedents in another early work: Landscape, Gloucester of 1922 (private collection), a small panel painted at the height of Davis’s experiments with Synthetic Cubism. The connections made in that panel with visible reality—the water, noted as white dashes against a black ground; the land, as red and blue dabs against creamy white; conventional landscape motifs in stylized profiles—become wholly abstract, angular shapes in Memo No. 2. In Landscape, Gloucester, the houses at upper right profiled against a blue ground that also reads as sky become black forms—negative shapes—outlined by white in Memo No. 2. The sailboats at upper left are translated into a jazzy parade of red triangles.

It had long been Davis’s practice to return to his previous work. He frequently rephrased and refined earlier compositions, not just to reexamine a theme but also to re-energize his art. As critic and curator Katharine Kuh explained, “Davis relied on what he called the ‘structural continuities’ between his paintings to brace and inspire him. He told me that he had ‘no sense of guilt’ when he reused designs and motifs he had conceived years before. ‘The past for me is equal to the present,’ he said, ‘because thoughts I had long ago and those I have now remain equally valid—or at least the ones that were really valid, remain valid’.” [9]

Memo No. 2 is the end of a sequence that also includes Colonial Cubism of 1954 (Walker Art Center). That painting’s title is a witty reference to Davis’s project of translating that most French of modern styles—Cubism—into an American vernacular. It recapitulates the silhouette and imagery of the 1920s painting. But Davis added a number of elements to the earlier structure, notably the free-floating circles at upper right and the star at lower left, and then used them again in Memo No. 2. There are additional “structural continuities” that link Memo No. 2 to other recent works: the black, white, red and green color scheme is shared with Lesson I (1956; Yale University Art Gallery), among other paintings. The right half of the picture, composed of angular white calligraphic lines against a black ground, parallels the design of Memo (Smithsonian American Art Museum), which is itself an updating of another Gloucester painting, Shapes of Landscape Space (1939; Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York).

The final motif of Memo No. 2 is the artist’s signature, which here, as in most of Davis’s paintings, is a carefully considered element of his overall design. These signatures have been described as “look[ing] as if [they] were squeezed out of a toothpaste tube,” and seem to be a spontaneous addition, another jazzy improvisation, but in fact the composition of Memo No. 2 would be much weaker without it. Davis added it at the very end, only a few weeks before his solo show opened at the Downtown Gallery. [10]

Memo No. 2 offers an informative summary of Davis’s method in the 1950s. As Kuh characterized it, he “developed an idea. . .and continued to recast it until it became a tremendously overpowering final picture.” [11] He gathered favorite shapes, which he turned, revised, and recombined, moving them from a descriptive space to an abstract one, and from highly stylized, almost recognizable objects to almost totally non-representational forms, with witty transpositions occurring along the way. The puffy clouds from Landscape, Gloucester still linger in Memo No. 2, for example, but now are black bulbous shapes contained by a thick white line. Memo No. 2 is relatively rare in Davis’s oeuvre for having no words or realist cues to hold his abstraction in check. [12] It is his title—does it refer to memorandums, or to mementoes?—that brings the painting back to connections with the objective world that Davis insisted was at the root of all his art.

Davis’s work continued to be highly visible and highly regarded through the 1950s and early 1960s (he died in 1964), up to the present day. After his 1956 show at the Downtown Gallery, he was represented in many group shows and was the subject of several monographic exhibitions, notably a solo show organized by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis that traveled to several museums, including the Whitney, in 1957, and a highly regarded show of recent work at the Downtown Gallery in 1962. Though not as prolific as he once had been, in the last decade of his life he still turned out, on average, five or six major paintings a year, and sold them promptly and for hefty prices: in October 1959, for example, the Whitney Museum purchased his recently completed The Paris Bit for $13,500—nearly $140,000 today. Davis won many honors and awards in those years. He was elected to the National Institute of Art and Letters in 1956, won the Solomon R. Guggenheim International Award in 1958 and again in 1960, and the Temple Gold Medal at the Pennsylvania Academy in Philadelphia and the Logan Medal and Prize at the Art Institute of Chicago in early 1964.

Although Davis had long since set aside his intense political activism of the 1930s, he continued his artistic activism throughout his later years. Even at the height of enthusiasm for Abstract Expressionism, he remained a highly sought after defender of his brand of objective abstraction. He served on panels such as the Museum of Modern Art’s “What Abstract Art Means to Me” (1951), with de Kooning and Robert Motherwell among the other speakers, and “The Place of Painting in Contemporary Culture,” the keynote session of the American Federation of Arts’ landmark conference in Houston in 1957. [13] During this period, scholars, critics, and curators repeatedly made the case for his continuing relevance despite the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism. In 1957, the New York Times published a feature asking the question “What art will endure?” It explained, “The New York Times Magazine recently asked a number of prominent American museum directors to name an American work of art, done since World War II, that they believed would endure…. Paintings by Stuart Davis received the most nominations, with Jackson Pollock the runner-up.” In the 1960s, Brian O’Doherty dubbed Davis “the most American of American Abstractionists” and observed that his work “was never out of date.” The avant-garde sculptor Donald Judd cheered, “Davis, at sixty-seven, is still a hot shot.”

Even as his health declined, Davis’s pictorial energy remained strong. He remained active as a painter and as a defender of abstraction to the very end of his life. In her reminiscences, Katharine Kuh offered perhaps the finest tribute to late works like Memo #2: “As Davis grew older and weaker, his visual logic grew tougher and his work became stronger: the late paintings are incandescent.” [14]

—Carol Troyen

[1] [Dorothy Seiberling], “Jackson Pollock: Is He the Greatest Living Painter in the United States?” Life 27 (August 8, 1949), pp. 42-45; “Are These Men the Best Painters in America Today? A Look Poll Gives the Opinion of Forty Art Critics and Curators,” Look 12 (February 3, 1948), pp. 44-45.

[2] Pollock’s biographers described him being as part of “the regular lunchroom crowd that craned to hear the lively dialogue between Arshile Gorky and Stuart Davis, who had just joined the faculty.” Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (New York: Clarkson N. Potter Inc., Publishers, 1988), p. 206.

[3] Barbara Haskell, “Stuart Davis: A Chronicle,” in Harry Cooper and Haskell, Stuart Davis: In Full Swing (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1916), p. 203; Davis, “For Internal Use Only,” in Aline B. Louchheim, “Six Abstractionists Defend Their Art,” New York Times Magazine, January 21, 1951, quoted in Haskell, p. 202.

[4] Davis, quoted in Haskell, pp. 209, 202.

[5] Ibid., p. 211.

[6] The Guggenheim Museum had purchased Cliché (1955) before the exhibition opened; the Hirshhorn acquired Tropes de Teens (1956) from the show.

[7] Stuart Preston, “Highly Diverse One-Man Shows,” New York Times, November 11, 1956, p. 156; Hilton Kramer, “Month in Review,” Arts Magazine 31, no. 2 (November 1956), pp. 54-55.

[8] O’Doherty, “Art: Paintings of the Honk and Jiggle,” New York Times, May 1, 1962, p. 34.

[9] Katharine Kuh, “Stuart Davis and the Jazz Connection,” My Love Affair with Modern Art, ed. Avis Berman (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2006), p. 116.

[10] O’Doherty, “Honk and Jiggle.” According to the editors of the Stuart Davis catalogue raisonné, Davis signed the painting on September 26, 1956. Ani Boyajian and Mark Rutkoski, eds., Stuart Davis: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 3 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007),no. 1696, pp. 415-416.

[11] Kuh.

[12] O’Doherty, “Stuart Davis: Colonial Cubism,” American Masters: The Voice and the Myth in Modern Art (New York: E. P. Dutton, Inc., 1974; paperback edition, 1982), p. 74.

[13] In his remarks, “The Easel is a Cool Spot at an Arena of Hot Events” (later reprinted in Art News), Davis argued vehemently for the superiority of objective over subjective abstraction. See Haskell, p. 212.

[14] “Will This Art Endure?” New York Times, December 1, 1957, p. 281; O’Doherty, “Honk and Jiggle;” O’Doherty, “Major American Artist,” New York Times, June 26, 1964, p. 26; Judd, “Stuart Davis,” Arts Magazine 36 (September 1962), p. 44; Kuh, p. 116.

Provenance

The artist;[Downtown Gallery, New York];

Mr. and Mrs. James Schramm, Burlington, Iowa, January 3, 1958;

[Middendorf Gallery, Washington, D.C.];

Southwestern Bell Corporation Collection, St. Louis, Missouri, December 2, 1987;

[Martha Parrish & James Reinish, Inc., New York]; to

Private collection, Boston, Massachusetts, July 2001 until the present

Exhibitions

The Downtown Gallery, New York, Stuart Davis: Exhibition of Recent Paintings, 1954-1956, November 6-December 1, 1956, no. 4Felix Landau Gallery, Los Angeles, California, Marsden Hartley, Stuart Davis, John Marin, Georgia O'Keeffe, Max Weber and Charles Sheeler, April 22-May 11, 1957, no. 2

Boston Festival, Massachusetts, May-June, 1957

Mead Art Building, Amherst College, Massachusetts; Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, Art of the Twentieth Century Collected by James S. and Dorothy Schramm, October 27, 1961-February 4, 1962, no. 7, illus. on cover

Cedar Rapids Art Center, Iowa, The Collection of James S. and Dorothy Schramm, September 14-October 22, 1972, no. 7

Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, Iowa Collects, 1973

Washburn Gallery, New York, Major American Paintings, June 1-30, 1987, no. 2, illus. on the cover

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California, Stuart Davis, American Painter, November 23, 1991-June 7, 1992, no. 153

Salander-O'Reilly Galleries, New York, Stuart Davis: Major Late Paintings, April 9-May 11, 2002, no. 10, illus. in color

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, Stuart Davis: In Full Swing, June 10, 2016-January 8, 2018, no. 57

Literature

Lowery Stokes Sims, Stuart Davis, American Painter, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1991, pp. 105, 159, 284, 285, 286, illus. p. 285 (as incorrect title, Colonial Cubism)Walter Hopps, et al., American Images: The SBC Collection of Twentieth-Century American Art, New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with Southwestern Bell Corporation Communications, 1996, p. 76, illus. p. 117, pl. 60

Patricia Hills, Stuart Davis, New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1996, p. 150, n. 45

Ani Boyajian and Mark Rutkowski eds., Stuart Davis: A Catalogue Raisonné Volume III, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2007, no. 1696, pp. 415-416, illus. in color

Barbara Haskell, Stuart Davis: In Full Swing, Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016, p. 128